Got another ad today! Please spare Pressmaster DMCC a click if you can. All ad revenues, from this and other ads, will go to something special I have planned.

Whenever you pick up your bib for a running race, as I did Friday evening for the Philly Half—sorry, the Dietz & Watson Philadelphia Half Marathon, sponsored by the City of Brotherly Love (and Sisterly Affection)’s premier maker of gabagool, honey baked ham, and sundry other deli delicacies—the volunteers will hand you four safety pins, dug out from an industrial box of safety pins. You use them to pin the bib to your shirt, your shorts, or, if you’re a public masochist, your bare chest, then you run your race, and then you’re faced with a dilemma: What do you do with these safety pins?

Or maybe it’s not a dilemma for you. Maybe you drop them in the trash. Or maybe you’ve got a properly sized, easily opened and closed container for safety pins that you keep within reach because you use safety pins all the time for a variety of reasons. I don’t know. But for me, for a very long time, it was not a dilemma at all. I just threw them away.

And for this I wish to apologize to safety pins: I’m sorry.

It’s not that I value safety pins in some fundamental way. I don’t esteem them as an emblem of 19th-century manufacturing genius, and I certainly don’t need to use them in my daily life. I’m only generally concerned about not adding waste to the world, which has nothing to do with safety pins in particular.

What I feel bad about is that our time together—the safety pins and me—is so short. Consider for a moment the lifespan of the safety pin: It begins as iron ore deep within the earth, from which it’s mined and smelted with carbon and a bunch of other elements with awesome names—molybdenum! vanadium!—to create spring steel, which I have only just learned exists and which has high tensile and yield strengths. From there, the steel is processed into safety pins; I’m told there are two U.S. companies that make them, and who knows how many overseas. Likely billions of safety pins are manufactured every year, and they’re sent out in boxes to warehouses, and from there to retailers or wholesalers, and eventually some of them wind up attaching bibs to chests, or holding your pants up when your zipper fails, or in the ears of throwback punks.

More after the ad…

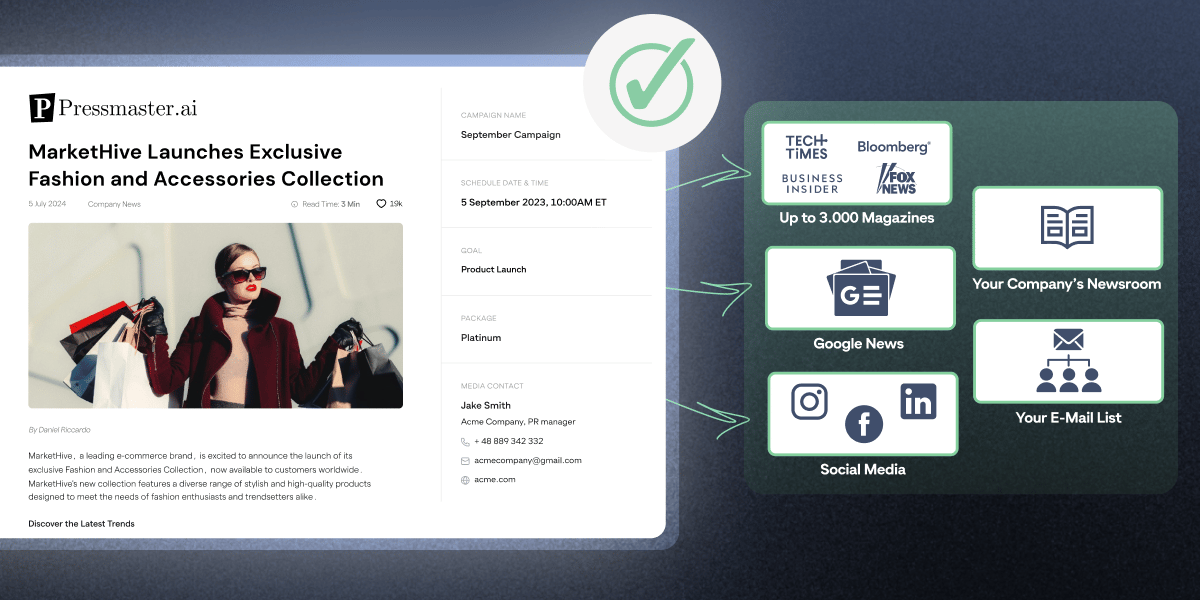

Building trust and increasing sales has never been easier

As a business owner, you know how important PR is to your company's success.

But the challenge of maintaining a consistent media presence can be overwhelming.

Now imagine being able to publish unique content to your website newsroom, social media and top magazines with just A FEW CLICKS.

Without a bunch of expensive tools...

Without a PR agency...

Or even a lot of time (because AI automates 98% of your work 🤌)...

Pressmaster.ai makes it a reality:

In other words, the safety pin is the result of years of work—of industrial and business processes that were themselves refined over a century and a half—all designed to put the safety pin right into our hands (and without stabbing them; it’s a safety pin, you know?). And then, days, hours, or minutes later, we’re done with it, and it vanishes into the trash, where it will live forever in the bowels of a landfill. Our time together, the moments for which the safety pin was expressly created, is but the tiniest fraction of the safety pin’s lifetime. And that’s what I feel terrible about.

The same goes for pens. In my 50 years on the planet, I have never once used up a pen, writing or drawing with it until the ink finally ran out. If I had to guess, I’d say I’ve lost 90% of the pens that have ever come into my possession. One day I had them, in my pocket or backpack or desk drawer, and the next: Poof! It was as if they’d never existed. For the remaining 10%, I’ve owned them long enough that the ink simply dried out and failed to flow. I threw those away. If you are a pen with any sense of ambition, you do not want to come anywhere near me.

Surely, much of this is intentional. As a species, we are rather unconcerned with waste, and I won’t even try to count the number of objects we deal with that are designed to be wasted immediately, as if throwing them away was the entire point of their manufacture, and recycling a fantasy. It should be obvious that this is not good, and that a couple of centuries of this has put mankind, and the planet we live on, in a precarious position.

But I’m less personally concerned with the physical waste here than the emotional or spiritual waste. All that time, all that effort, all that innovation—to build a safety-pin-making machine that can crank out 3 million a day!—for a utility that will be forgotten within an hour. Was it worth it? Did it mean anything? Is this an inescapable component of what Haruki Murakami would call late capitalism? Is the relentless creation of billions of safety pins every year an ultimately pointless task, one we don’t ever bother to question because, from time to time, we do need safety pins?

It’s humbling to ponder. Is the safety pin passing through our lives, or are we passing through its? Perhaps, from the safety pin’s point of view, the time spent in my care is a blip unworthy of consideration. After all, there has been so much excitement before and such an unpredictable journey ahead! Who cares about this brief interregnum of being attached and removed once or twice when eternity awaits? The safety pin may have an entirely different raison d’être from what we assume. Perhaps there will come a day when we need its ore again—when a great safety-pin harvesting will gather them all from junkyards and junk drawers to be re-smelted into skyscrapers, starships, or zombie-poking spears. Perhaps the safety pin’s fate lies beyond our ken. Perhaps the inner life of an everyday object is unknowable.

The easy resolution for me would be to stop throwing away safety pins, and just remember to bring my own safety pins to the next race. Okay, I think I can do that. Eventually, though, they will get rusty or crusty with sweat, grow stiff and unusable, maybe even break. And then, finally, months or years later than anyone expected, into the trash they’ll go, to begin the next phase of their journey. Oh, the stories they’ll have to tell! The wind in Philadelphia, the sun in Brooklyn, the cobblestones of Rome, the trails of Griffith Park! I sincerely hope there are some pens in their audience, and that they forgive me, too. 🪨🪨🪨