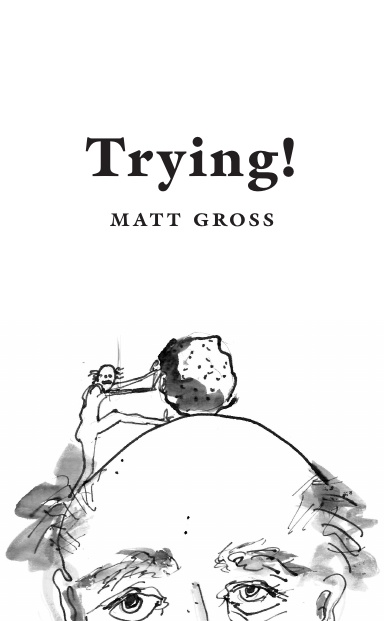

Before we get into today’s essay, I’ve got an announcement: The Trying! book exists! Check it out:

It’s a fine, fine production, with a lovely introduction by Hugh Garvey and kooky, delightful illustrations (including that 😙🤌 cover) by Aliza Gans. It’s just 160 pages long, and comes in a cute small pocket-book format, so you can take it everywhere, or prop it up next to the toilet, where it belongs.

How can you get your hands on a copy? It’s easy:

Become a paid subscriber! Upgrade your subscription to any of our paid tiers by the end of 2024, and I will send you a copy.

Get me 5 new subscribers! Surely you know a few people who appreciate good, occasionally unhinged writing on myriad topics? For every five of them you get to sign up, using the referral code you’ll find below, under “Upcoming Rewards,” I’ll send you a copy of the book.

Buy one—or more—from the site above! Priced at just $12.34, the Trying! book makes an excellent gift for the literate weirdo(s) in your life. It likely won’t arrive in anyone’s mailbox by Christmas, but literate weirdos don’t live according to strict calendars.

Okay, that’s enough self-promotion for one vanity newsletter for one day. Let’s launch into the essay—right after the referral program blurb…

The Sweet Smell of... Wait, What Is That?

Once a year, if I’m lucky, I get to take my wife and kids back to Amherst, the Massachusetts town where I spent the bulk of my childhood. Usually, we’re just passing through, on our way to or from Vermont or the Boston suburbs, so we’ve rarely got time to explore my old haunts—the houses I lived in, the schools I attended, the nameless creek running from McClellan Street down to a UMass parking lot. Mostly, we focus on just one thing: ice cream.

The Pioneer Valley has had excellent ice cream almost my whole life, thanks in large part to the region’s thriving dairy industry. (As of 2023, there were still 54 dairy farms operating in Franklin, Hamden, and Hampshire counties.) When I was a kid, we were regulars at Herrell’s, where Steve Herrell pioneered the concept of mix-ins, and at Bart’s, both in Northampton and in Amherst. Today there a dozen more ice cream brands and stands, but the two I make a beeline for now are Flayvors of Cook Farm and Hadley Scoop at the Silos. The purity of the milk, the intensity of the flavors—the kids and I love them.

There’s just one problem: the manure.

See, the dairy farms that supply these (and/or other) ice-cream makers happen to be right next to the stands themselves, in a part of Hadley, Amherst’s neighbor, that is rife with dairy farms. On a warm summer’s day, the inevitable byproduct of dairy production produces a scent that pervades the landscape and penetrates first your car, then your nostrils. To Jean and the kids, it smells like shit.

To my nostrils, however, the smell is wonderful, sweet and rich and organic. In it I can sense decay intertwined with new life, the endless cycle that keeps us going. I love it. One of the houses we lived in was just down the road from these farms, and we’d go past them all the time, by car, by bike, or on foot, on the way to or from the mall. When the wind blew just right, we didn’t have to leave home at all—the manure smell came to us. It’s the scent of my childhood, or a particular part of it, and because I had a happy childhood, or because I smelled the manure in the run-up to seeing a movie or buying toys at the mall, the associations are inextricably interlinked. I can’t help but love it.

And on that I have some decidedly mixed opinions. On the one hand, I’m happy, proud even, that I can perceive a nearly universally derided aroma as pleasant and evocative. I don’t have to shy away from it, pinch my nose, whine and complain until it’s gone. I can inhale deeply and relish every molecular interaction. I don’t even have to force myself to do so—it’s right there in my memory, built into my core functionality. I sniff, therefore I am.

And that’s the part I have a problem with. Because even though this is a positive response, I’m not actually in control of it. I haven’t decided I like the smell of manure—I just do. This is how smells work. Here’s a pretty tight scientific explanation of the connection between scent and memory:

Smells are handled by the olfactory bulb, the structure in the front of the brain that sends information to the other areas of the body’s central command for further processing. Odors take a direct route to the limbic system, including the amygdala and the hippocampus, the regions related to emotion and memory.

To experience this, and to know you’re experiencing this, is a wonder of human evolution. I’ve had moments when a passing scent will instantly transport me to my early 20s in Ho Chi Minh City, whose streets were defined by moped exhaust, ripe fruit, grilling meat, and inadequate sewers. I’ve always loved petrichor—the smell of dust in the air after rain—though I can’t pinpoint when or why I first became aware of it; the connection feels almost genetic, stretching back to humanity’s first, self-conscious awareness of the natural world. I don’t know the evolutionary basis for the direct route to the limbic system, but I certainly appreciate it.

Except when I don’t. Because those bonds of memory and emotion are so strong, they’re hard, almost impossible, to break. But break them we should, because to accept them is to accept that we are ruled by nostalgia, one of the most corrosive forces at work among our species today.

Look, I’m not immune to nostalgia myself. This reasonably high-quality newsletter traffics in it from time to time, as I dredge up memories of my childhood and young-adulthood and put them to service crafting a half-assed existential worldview. But I am trying, always, to question those memories. Did I get the details correct? What did I miss at the time? How could I have been misinterpreting events through the decades? I know my memory, though voluminous, is riddled with inaccuracies, misperceptions, gaping holes, and outright figments, and the last thing I want is simply to trust it.

But many people do! They succumb to the power of nostalgia without a fight, let alone a query. They assume that because they were happier once upon a time—often when they were children or teenagers or young adults—things were better then. Never mind that youth, with its lack of responsibilities and its easy freedom to imagine the future, always looks better in retrospect. Never mind that a whole political cohort relies on nostalgia, despite the internal contradictions: some long for the 1990s, while other see the ‘90s as vastly inferior to the ‘70s, which are trashed by those who put the ‘50s on a pedestal. Life was always better “before,” even if we were too young to understand what was happening then—even if we did not even exist then.

This is not to say things weren’t better before. (As we all know, I’ve got a soft spot for the “applecore” era.) But it’s also not to say things were necessarily worse. They were just different. The past is a home we can never return to1, and the future is another country (and, eventually, the undiscovered country). We are nothing more than migrants, and the only constant, as Octavia Butler argued in her Parable books, is change, which rules our lives as does a god. But as well adapted as we humans are for it, change remains hard to wrap our heads around—so it always goes with the divine. We are built to identify patterns and act accordingly, but when those patterns shift, and keep shifting, we get lost, and in our confusion and fear we look back to the patterns we know will never change, because they’re locked away deep in our memories, in an era of certainty, absolutes, and trust.

As adults, though, we can’t afford to think this way. We can’t just say, “I know this because I remember this.” We have to question the things we think we’ve always known to get at what’s true and what’s false, what works and what fails. If there’s any hope of building trust with younger generations, and of building a future at all, we can’t rely on the accident of the limbic system. We can’t trust our own hallucinations.

That’s not to say you shouldn’t allow yourself the occasional dip in the sweet bath of nostalgia. Those memories, and the emotions they bring, are real to us, if not always really real, and we shouldn’t deny ourselves a bit of pleasure now and then, or even a bit more often. But as with any bath, eventually you get all wrinkly and need to towel off, get dressed, and head to work, leaving the waters of time to drain away. Don’t worry, you can always refill the tub. But the goal here is to know what you’re thinking and feeling, and why, so when the time comes for you to make important decisions, it’s you, not your autonomic systems, that’s in control.

In other words, I love the smell of manure now because I loved the smell then and because I choose again to love it now. Why not? It’s just a smell. So when summer arrives, we’re still going for ice cream in Amherst. But I might take a different route to get there. 🪨🪨🪨

Notes

Hence nostalgia: “nostos” meaning homecoming + “algia” meaning pain.