Today’s advertiser is Go-to-Millions. Although Beehiiv rules forbid me from asking or encouraging you to click the ad, if you do so, of your own free will and according to your own moral principles, each click will earn me $1.68.

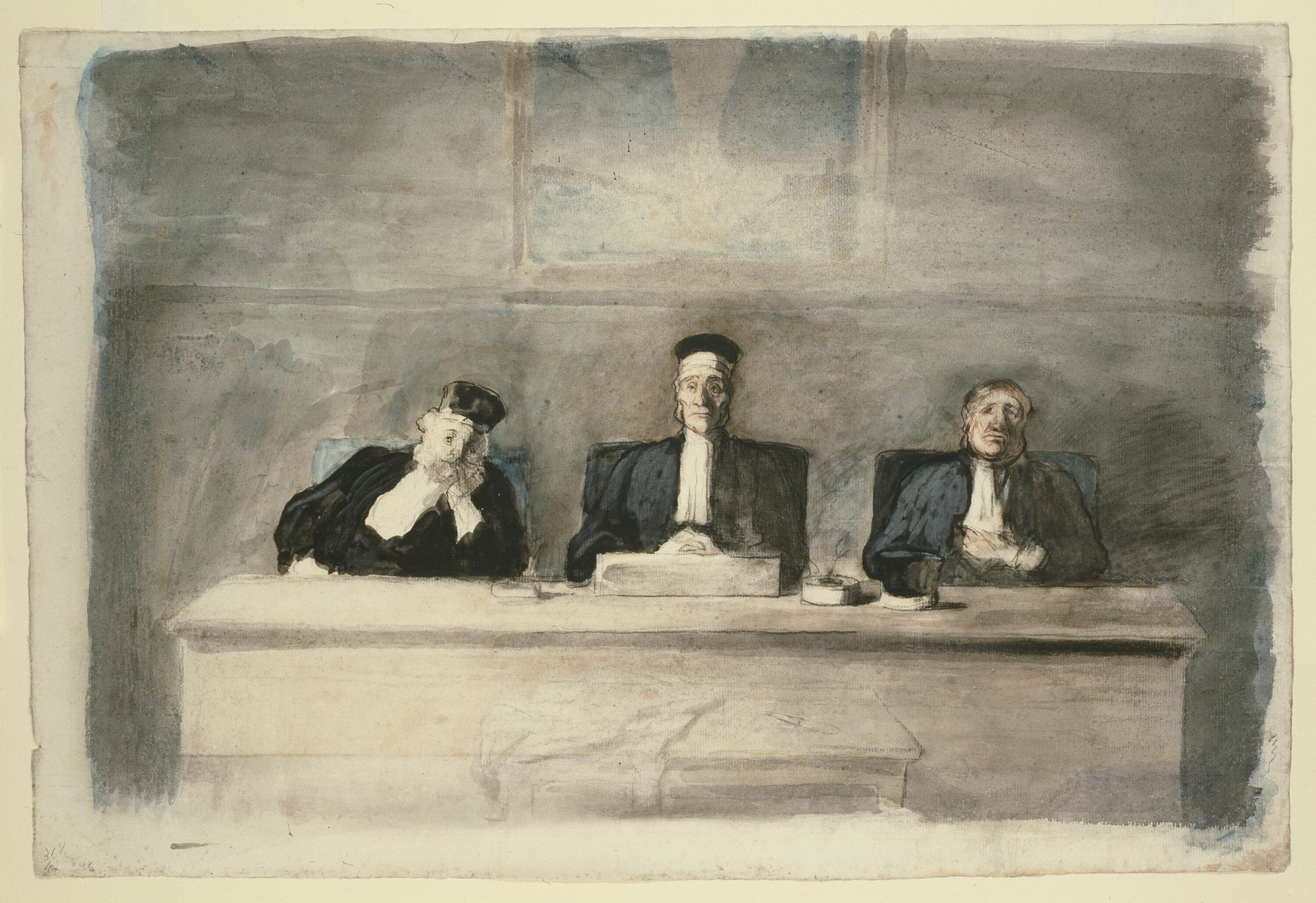

“The Three Judges” (1858/60), Honoré Victorin Daumier

Early in the 21st century, I was called to jury duty at Manhattan criminal court — an unexpected joy! I know some people hate jury duty, a resentment so common it’s idiotic cliché, but I love it: How often do I get to hold the fate of my fellow citizens in my own two hands? Their fortunes, their freedom, their very lives depend on me and my fellow jurors to take seriously the process, analyze the evidence and arguments, and render fair judgment. The power! The power! And while, yeah, I can be a smart-ass about most things, I do believe in the law and the structure of the system to provide something akin to justice. Plus, I tend to be very decisive, so I make an excellent juror.

The case I was assigned to was a juicy one. A middle-aged German woman was accused of defrauding the elderly Upper East Side woman, well into the throes of dementia, she had been caring for. She had allegedly signed checks to herself in her employer’s name. They weren’t huge sums, there was no violence, but this was exciting in the sense that it appeared to be a real crime that had resulted in an actual trial. No plea deal, no major evidence deemed inadmissible and the case thrown out of court. The defendant was weird, tall and gawky and unpolished, an immigrant from another, more distant era. It wasn’t just her accent but her whole awkward affect; she did not present well, and I wondered why her lawyer let her take the stand. That this case had even gone to trial suggested she was stubborn beyond reason, with faith in her own innocence, but her inability to communicate clearly or relate to the courtroom probably doomed her from the get-go.

Except… Except that the case hinged on a specific set of evidence: the checks the defendant had allegedly forged. A handwriting analyst who’d been called to the stand could not say definitively that the signatures on the checks matched the defendant’s handwriting, and so it was left to us, the jury, to decide. We had four checks in all, two of which both prosecution and defense agreed were signed by the alleged victim, with the other two in question. If we decided they were forgeries, the defendant was guilty. If we had reasonable doubt, she would go free.

To me, our process seemed clear: We had two authenticated signatures, so if the other two diverged in significant ways, we could say they’d been forged. When I looked at them, I felt that some of the letters were indeed different — maybe a y, maybe an s, this was a long time ago, so I don’t remember precisely — and different enough that I was confident in declaring them forgeries. Like I said, I tend to be decisive.

“The True American” (ca. 1874), Enoch Wood Perry

Not so the other jurors. To many of them, because the official handwriting analyst had not been able to render judgment, they themselves were unwilling to undertake any further study. No matter how I tried to point out the discrepancies between the handwriting styles, they simply would not consider it. They were not experts, they said. How could they possibly decide?

This was maddening. It was so clear to me what we needed to do, but they seemed unwilling to engage with the evidence — or, as I saw it, to use their goddamn brains.

In the end, I could not persuade them. (Maybe my own awkward affect did not help?) Still, enough jurors mistrusted the defendant that we came to a compromise, finding her guilty on several counts, some of them lesser, while clearing her of others. I don’t know if what we did was strictly within court guidelines, but it felt like justice.

More after the ad…

🪨

Your Boss Will Think You’re an Ecom Genius

You’re optimizing for growth. You need ecom tactics that actually work. Not mushy strategies.

Go-to-Millions is the ecommerce growth newsletter from Ari Murray, packed with tactical insights, smart creative, and marketing that drives revenue.

Every issue is built for operators: clear, punchy, and grounded in what’s working, from product strategy to paid media to conversion lifts.

Subscribe free and get your next growth unlock delivered weekly.

🪨

All these decades later, the case still bothers me. If I were a reporter rather than an essayist, I’d dig into the court records, find the name of the defendant, and learn what became of her. Did she serve time? Did she remain in New York, or was she deported? How had she wound up in New York in the first place? Had she grown any better at presenting herself to an unfeeling public?

But that’s just prurient curiosity — let’s leave her to her own private fate. What I really wonder about is this: If the same trial were to be held today, in a United States that has denigrated expertise and authority and elevated “do your own research,” would more of the jurors listen to my argument? Would I even need to persuade them that they had the intellectual capacity to discern authenticity from forgery? Or would I now be the cautious one, warning that even the trained professional called to the stand could not make a definitive pronouncement?

On the one hand, I do believe in the ability of human beings to think. I wouldn’t be writing these essays if I didn’t! We can think, discuss, create, make mistakes, try again, and eventually figure out so much in this world, from the 9,000-year domestication of teosinte into corn to building AI apps to deepfake revenge porn. Our brains consume approximately 20% of our energy every day, and that’s because they are powerful organs — if we use them that way. Often, we don’t. We watch reality TV or doomscroll the night away or stare at our phones as we walk down the street and into the paths of buses. Okay, that’s not entirely fair. We just might not spend our days thinking particularly hard about anything. I do all the above. It’s fine. No judgment here, except for the one I’ll pass on myself: I feel guilty about all the time I waste not using my own goddamn brain.

Still, I use it enough that I imagine that I could learn anything if I really wanted to. I could go back and finish my math degree, even if I had to start over from scratch. I could come to understand quantum mechanics, learn to knit, appreciate poetry, study Japanese or Arabic or C++, do well enough on the LSAT to get into law school, manage basic maintenance of older automobiles. I don’t mean to overstate my abilities. I don’t expect I would become an expert in any of these subjects, certainly not on par with the world-class newsletterer you see before you. But decent comprehension and moderate ability? Those are within my meager reach! I’ve spent my entire life trying to learn things, and learning how to learn, and I’d like to believe I’ve got a bit farther to go.

At the same time, I’ll acknowledge some limits. I’m never going to be fluent, or even really reasonably conversational, in Mandarin or Vietnamese or any other tonal language. Perhaps not unrelatedly, I’m never going to master a musical instrument or sing well. There are some basic aural-neural connections that just don’t work in my head the way they might have if I’d focused more on music when I was younger and my brain more plastic. Throw drawing and painting in that unlikely bucket, too. Or maybe I’m giving myself short shrift — put enough time and effort in, and my synapses would open up to new possibilities. Perhaps judicious use of LSD would help?

So for the moment, I’m stuck here, in the place we’re all stuck. There are things we understand and things we don’t, things we will come to learn and other things we will never have a chance to grasp. And the thing I’m most trying to learn right now, as I work through this essay, revolves around the latter: What is out there that I don’t understand and never will, and how do I come to grips with that, both intellectually and emotionally?

These are questions that send me back into that jury room decades ago. Do I trust the expert or do I trust my own ability to reason? I am by nature a faithless skeptic and an overthinker. But overthinking has taught me to recognize the point where my knowledge and abilities end — I am skeptical of no one more than myself — and to see that reality continues on past them regardless. Whether we put stock in authorities or not is often immaterial; when they are acting in good faith, experts are merely the vehicles of reality, letting the rest of us know the universe acts in consistent ways that, though they may be alien to us, can be defined, tested, elaborated on, manipulated, and understood. Maybe not by you or me, or maybe not yet.

To accept this is painful. I’ve always tried, and sometimes succeeded, to think myself out of whatever situation I’ve been in. To tell myself I can’t — or, worse, don’t even need to — is wretchedness. I want to turn off my brain and trust the Force, as Luke Skywalker did, but only if I know the Force is real.

To decide — for I am, as I might have mentioned, a very decisive person — I turn again to our justice system. When faced with the unknowable, the incomprehensible, I consider reasonable doubt. Given what I do know, given all the evidence before me, does it make sense to trust or to mistrust, to accept or deny? And despite my reflexive skepticism and smart-aleck bravado, here I must tell the truth, and only the truth, on this stand I’ve erected: I want to trust, to accept, to find my way to reasonable faith in my peers and the universe they inhabit. Like Fox Mulder, and René Descartes before him, I want to believe. 🪨🪨🪨