“Chang and Eng, the Siamese Twins” (1836), Edouard Henri Théophile Pingret (1788–1875). Credit: The Wellcome Collection.

All throughout high school, my friends and I talked about this one movie we’d heard of and wanted to see. It was called Faces of Death, and it was no run-of-the-mill horror film. Instead, it was purportedly full of real footage of real people (and real animals) dying, or being killed, in all kinds of miserable ways. Accidents, mutilations, war, suicides, police shootouts — we didn’t really know, because we couldn’t find Faces of Death at any of our video stores in Tidewater Virginia. It had been banned or censored by numerous countries, so maybe that accounted for its absence from the shelves. But its reputation persisted, as did our interest, and one day, in 1991 or 1992, Faces of Death IV — one of its sequels — appeared at the video store. We rented it immediately.

Reader, it was not good.

The series had apparently always mixed real footage with staged events, and though this was gory enough for a bunch of teenage boys, even we did not buy it. The scene I remember best1 is of an ambulance flying down a street, running over a pedestrian, then loading the victim into the back of the vehicle and departing. Why, I wondered, was a camera there to capture this particular moment?

We had gone into this movie hoping for graphic violence of a kind we’d never before witnessed, video’d deaths that would reveal to us something of the nature of death — something inescapably real — but instead we were bored and disappointed. We’d learned nothing. We’d been had.

Now, after the events of the past weekend, I have to say: I miss those days.

Saturday was the Faces of Death experience I guess I’d been hoping for 30+ years ago. It began with the news that someone — eventually revealed to be ICU nurse Alex Pretti — had been shot and killed in an altercation with Immigration and Customs Enforcement in Minneapolis. One cell-phone video made the rounds of social media almost immediately: a pile of federal agents atop an almost invisible man, beating him and holding him down, until suddenly we see Pretti’s long legs kick up at an angle and the agents back off. (I watched without sound, so didn’t hear the gunfire.) He is dead.

Over the next several hours, more videos emerged, as they do: different angles, different timeframes, all of them adding their own piece of the narrative. What happened before? Did he speak to anyone? Did he have a gun? Was he holding the gun, or reaching for it? Since no one on the scene can predict the future, no one knows what details to focus on. These are wide shots, attempting to capture everything, whatever everything might be. This is not filmmaking. No close-ups, no flashbacks, no expository dialogue. The footage is intended to be archival, but is necessarily incomplete. The people behind the cameras don’t know what they’re seeing until it’s too late. And then, as more videos come out, serious news outlets race to reconstruct the events, syncing up the various clips, ticking some of them by in slow motion, circling guns and phones and badges for clarity, and finally deciding whether the videos contradict or merely “appear” to contradict accounts from the Department of Homeland Security, whose officials seem to have watched an entirely different movie from the rest of us.

As terrible as the news was, there was an exciting aspect to it as well. The way it rolled out — text messages, cryptic social media posts (“Be careful friends near 26th & Nicollet. Those fuckers just murdered another person.”), then a flood of images and videos, analysis and commentary — lent it palpable suspense. Anything might come next! Another clip, an Internet history, hyperbole from the government, quotes from the victim’s friends and family. Above all, I was hoping, as I often do lately, for an explanation, a crystal-clear and incontrovertible story of what took place and why it took place, so that we could all stop arguing and see — all of us see! — that a man had been killed because the government feels like it can kill people for no reason, label anyone in opposition a “rioter” or a “domestic terrorist,” and just get away with it.

By evening, as my family was preparing for the big snowstorm, the flood had slowed to a trickle, and the only thing that was clear was that everyone would go on arguing about what had happened in Minneapolis, with no resolution. The videos were not enough, and would never be, no matter how many new angles appeared in our feeds, and no matter how much we actually know what happened.

It was with this in mind that I tuned into Skyscraper Live!, Netflix’s live presentation of rock-climbing legend Alex Honnold’s attempt to free solo the 1,700-foot Taipei 101. Delayed a day by rain, Honnold would have no ropes, no safety net. If he slipped and fell, he would surely die, a fact he and his wife and every single one of the no doubt millions of viewers understood. This is precisely why he was doing it, and this is precisely why we were watching it — he was taking the ultimate risk.

And if he did fall and die, his fate would be captured by countless high-definition cameras. This was a production. There were cameramen on ledges, cameramen on wires, cameramen in a helicopter. People inside Taipei 101 were shooting videos of Honnold as he climbed by; they took selfies with him on the other side of the glass. He even took one himself, when after about 91 minutes he reached the tippy-top unscathed:

The crispness of that image is emblematic of the production. It was a lovely day, blue sky, gentle sunlight, air free of murkiness and smog. In shot after well-composed shot, you could see Taipei spread out below, its dense buildings giving way to a ring of mountains. Or you could focus in on Honnold, the careful and precise way he moved his feet, the tightness with which he pinched the skyscraper’s steel, his unnerving lightness as he hopped up each of the ten “dragon” features. Nothing here was blocked or fuzzy, nothing left to the imagination. Honnold was mic’d up, talking to the show’s hosts, to its producers, to himself. (His words on reaching the summit: “Siiiiick.”) No one will argue about what Alex Honnold did at Taipei 101, because every second of it — including preamble and aftermath — was captured from almost every angle imaginable2.

But that incomparable clarity is also somehow disappointing. Throughout the hour-and-a-half climb, my kids and I were locked into “can’t turn away” mode3. It was too stressful to watch, too stressful not to watch. Our hands were sweaty with empathy. But did we want to see him succeed? Or did we just not want to miss his fatal failure? Since he lived, I can say that once it was over, once he’d finished his selfies and started rappelling down to where he could catch an elevator, there wasn’t much to do other than marvel for a few more minutes at his superhuman abilities and his inhuman fearlessness the way we’d been doing more or less since 8 p.m. The lifespan of Skyscraper Live! had reached its natural end.

Frankly, I’m still trying to make sense of these two video “productions.” Both were realer than my high-school horror fantasies, therefore more terrifying. That I could see them in quick succession — hours apart, slotted in among pre-snowstorm errands and meal prep — is monstrous, but also a key feature of our flattened age. It’s everything, everywhere, all at once, produced by bullies and directed by morons.

Perhaps it’s better to focus less on the production and more on the protagonists, who are negative images of each other — identical opposites. One woke up knowing he might die, and that his death would be captured on video. The other could not have predicted his fate… though he could have suspected it. Each had a script he hoped to follow, and hoped the rest of their supporting cast would improv through it. And in each case, the difference between their survival and their annihilation came down to the tiniest of matters: a grip here, a step there. One second’s miscalculation and there would be — or there was — no second chance. I watched them knowing all of this, and hoping it would not also apply to me.

But it does, and to you as well. There will be sequels to each Alex’s story, and we’ll surely watch them, whether passively, as they flit across our feeds, or actively, staring in mute horror or following rabbit holes in a quest for answers that may not exist. One of those sequels, I fear, is coming very soon to a theater near you, and near me, and for that I hope we’ll be needed only as extras in crowd scenes, not as featured players. As much as we may crave attention, not all of us are ready for a starring role. The director, however, may have other ideas. 🪨🪨🪨

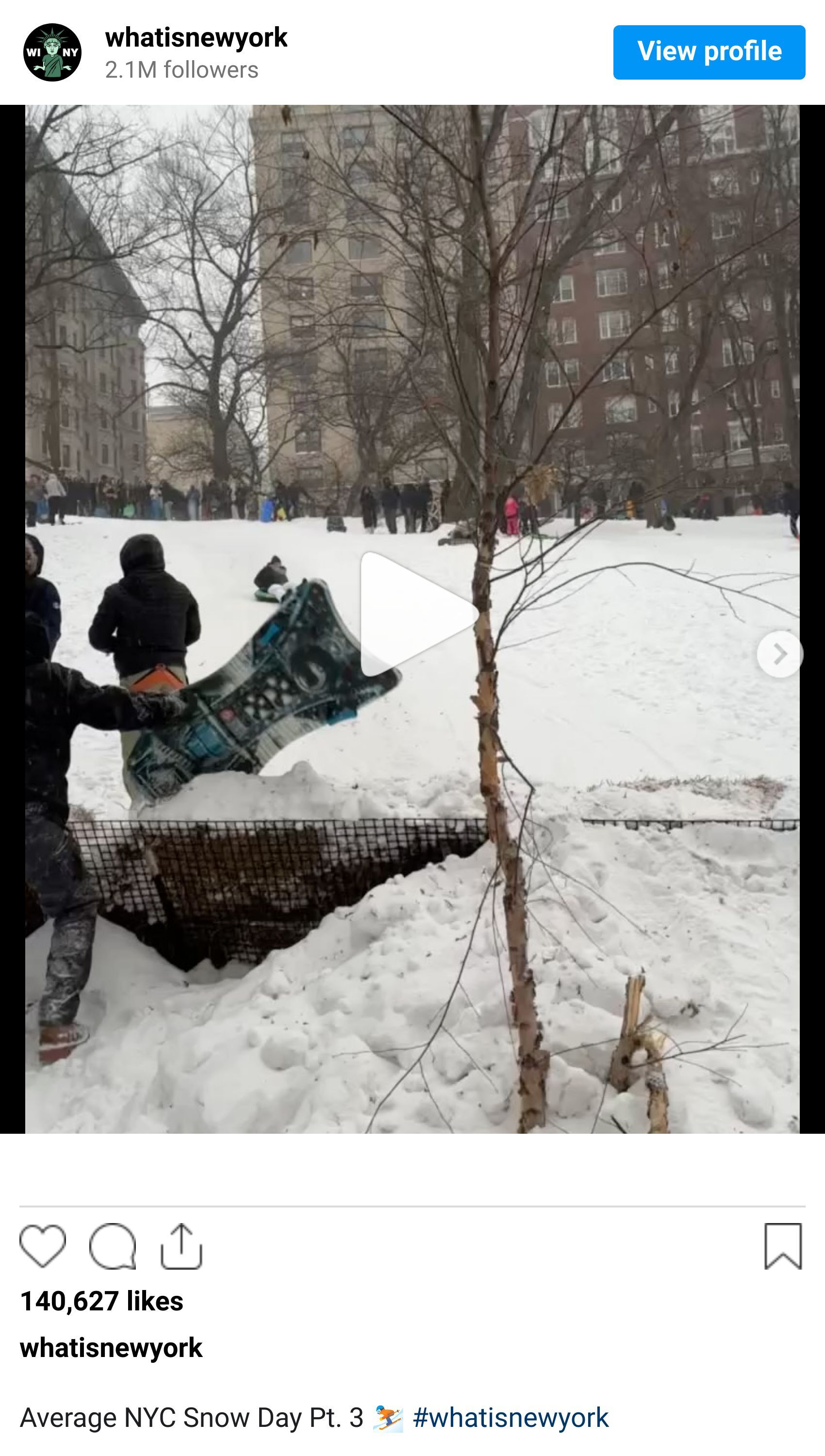

It’s Good and I Like It: Snow Day NYC

Some things in this world are still nice.

Read a Previous Attempt: Are you a domestic terrorist?

1 Disclaimer: I may be misremembering, of course!

2 Honnold was not wearing a GoPro or Meta’s Ray-Ban glasses.

3 My wife, though, kept asking if we could change to something else.