Today’s advertiser is Kajabi. Although Beehiiv rules forbid me from asking or encouraging you to click the ad, if you do so, of your own free will and according to your own moral principles, each click will earn me $1.68.

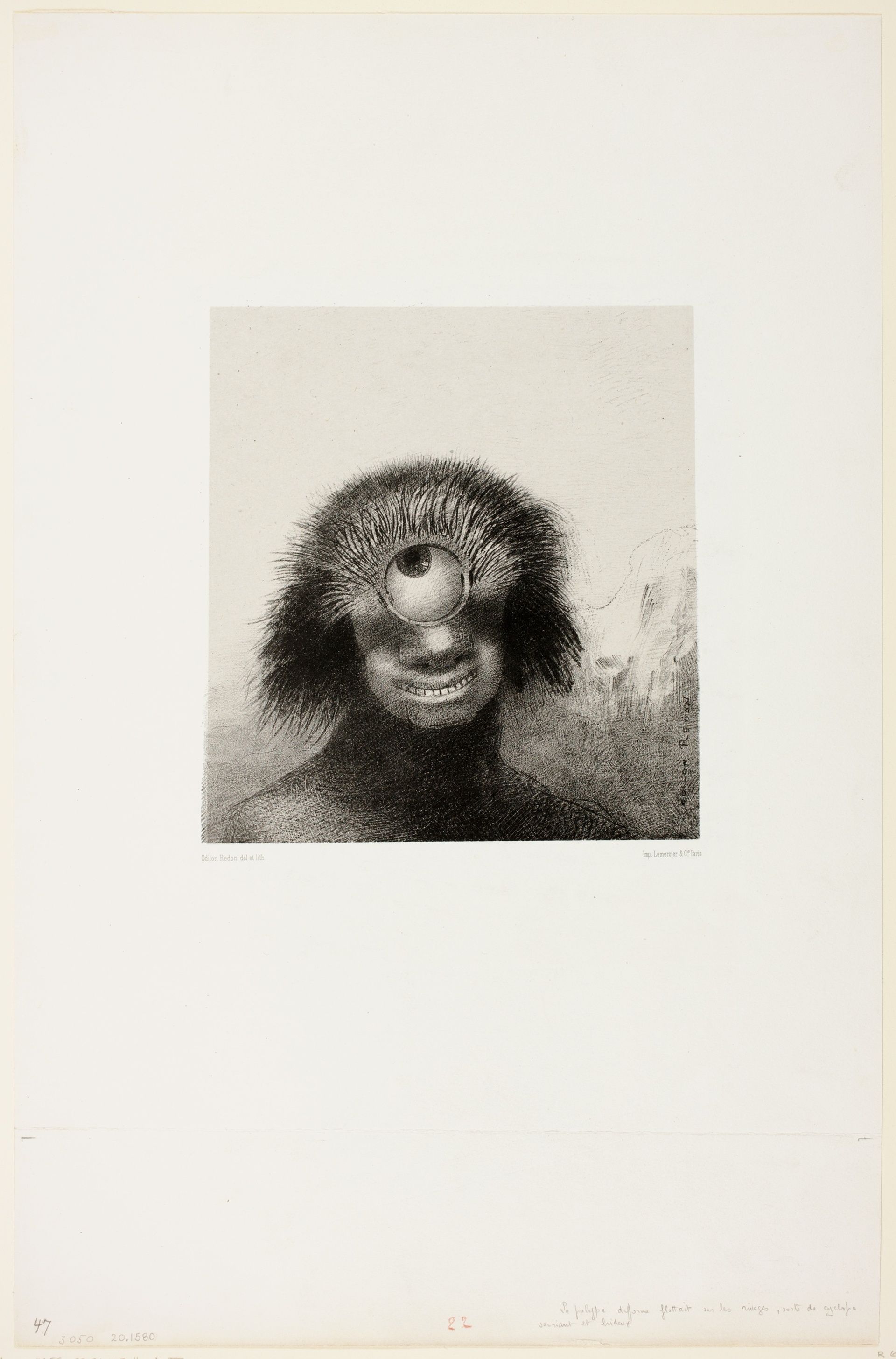

“The Misshapen Polyp Floated on the Shores, a Sort of Smiling and Hideous Cyclops” (1883), Odilon Redon

This past Sunday morning, my friends Tony and Ted and I drove one whole hour north from Brooklyn to the Teatown Lake Reservation, in Ossining, New York. It was a very crisp and sunny day, a few degrees below freezing, with only a few wispy clouds in the sky and a thin layer of ice on the water. The bare trees of the forest were stark and spindly; a large hawk perched in the branches stood out plainly.

This was the setting for the Taconic Road Runners Cross-Country Relay, a trail race that attracts just a handful of teams every year, many of them, it turned out, from New York City. The Front Runners, for example, were there in relative force — the team, founded in 1979, is NYC’s premiere LGBTQ+ run group and has 1,100 members. Meanwhile, our team, though it was founded around 2012, has perhaps seven or eight regular members. Our name: the Not Rockets.

If you tilted your head quizzically at that name, you are not alone. At the race, and at almost every running event we participate in, that’s how people reacted when we introduced ourselves — with confusion. Had they misheard us? Why would a team name itself something so weird, both vulgar and self-deprecating? One woman, part of the group organizing the race and the wonderful post-race pancake breakfast, gave us a “Bless your heart” smile. And when the results were posted online — we came in second, and ended the Front Runners’ “over 50” team’s five-year streak! — our name had been upgraded. Upstate, I guess, we’re now the “Hot” Rockets.

Look, I shouldn’t be surprised. For 51 years, I’ve felt misunderstood and out of place in this country. It’s right there in my name: I bear the weight of not only my Grossness but my grossness. My interests, my habits, my sense of humor are not the norm; I have a higher level of comfort with the horrifying (and often amusing!) ways that life can go sideways than most people. I’m not actually that weird. In reality, I’m pretty vanilla. But I’m weird enough to know better.

Still: Come on, people! After the last couple of decades of cultural shift — after the rise of niche interests and the splintering of the mainstream, the outing of everything private and the death of public politeness — shouldn’t we all have gotten used to oddity? We are we still weirded out by the weird?

More after the ad…

🪨

Be the Coach Clients Can’t Wait to Join

Maxed out training hours for clients? Here’s how to make 2026 the year you grow your business without burning out.

Kajabi has helped fitness professionals generate millions in online revenue by giving them the tools, strategy, and support to scale. That’s why we’re the go-to platform for instructors shifting into hybrid and online coaching.

Take advantage of our free ‘30 Days to Launch: Scale Your Fitness Business Online’ guide that will give you the step-by-step plan to combine in-person and online programs for more income, freedom, and flexibility.

🪨

There are several kinds of weirdness out there. Most famous is probably the weirdness of Austin, Texas, whose “Keep Austin Weird” slogan dates back to the year 2000. Back then, Austin was weird: a sleepy state capital full of bats and slackers, where a homeless man in a thong and high heels ran for mayor and came in second. Sure, South by Southwest was still a big deal, but because it attracted cool indie bands and tech evangelists at a time when neither of those represented billions of dollars. Austin was weird because it was out of step with America, and nowhere else in America wanted to be like Austin. Except, of course, for Portland, Oregon, which adopted its own Keep Portland Weird slogan around 2003.

What I find beautiful about these “keep it weird” movements is their self-consciousness: They are proud of their quirks, their rough edges, their inability to fit in, and the way the rest of the country looks askance at them — yet they also know their weirdness is threatened. (Because why else have the slogan?) And it’s threatened not just by the normalizing forces of the grown-up mainstream but by the corrupting power of capitalism. Austin and Portland understood that within their weirdness lay something special that both locals and outsiders actually liked and appreciated, and that while no corporate entity could conjure up those qualities in a boardroom, big business could certainly co-opt the existing weirdness, neuter it, and transform it into revenue. In Austin, that’s definitely what’s happened. In Portland, maybe not so much.

But weirdness does always come to an end. It thrives in darkness and isolation, but the arc of the last few centuries has bent toward light and connection. When the music critic Greil Marcus coined the phrase “the old, weird America,” in his book on Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes, he was referring to the characters who inspired an even older era of folk music: carnival barkers and conmen and roaming preachers, the doomed and depraved and liminal souls who peopled the states and starred in the songs. They were weirdos because they could be and because they had to be, since the mainstream would not accept them. Until, as the twentieth century wore on, it did, or the weirdos died out, and with them a way of life, and maybe an appreciation that not everything and everyone need be normal.

Yeah, I had to include this one.

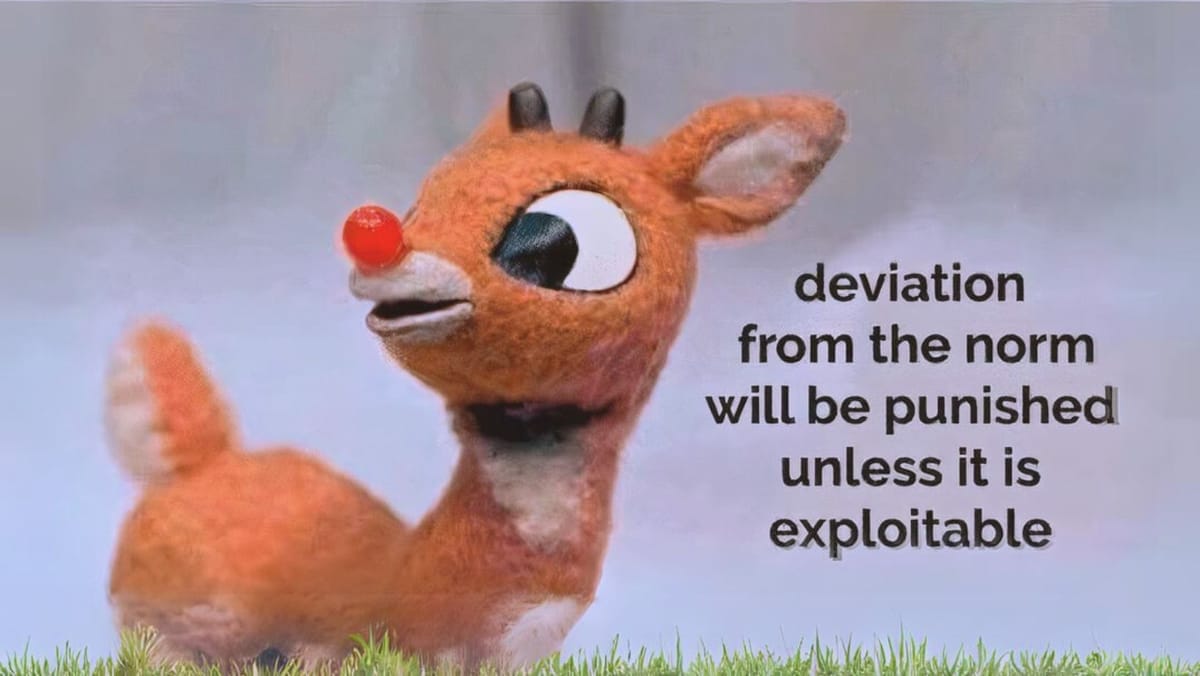

It’s harder than ever to be weird now. Thirty years ago, Beck could sing, “I’m a loser, baby, so why don’t you kill me,” and Thom Yorke could declare, “I’m a creep, I’m a weirdo,” and we loved them for it and made them stars. (Wait, were they being ironic?) I don’t see as much of that today. Because why be truly weird when you could be a tiny little bit less weird and cash in on what you’ve transmuted to mere quirkiness? Those who resist that temptation are rarities now. I can barely think of any. Maybe Chuck Tingle? Julio Torres? The fact that I know their names at all probably means they’ve long since crossed over into the mainstream.

So perhaps that also means weirdness continues to thrive today, somewhere just beyond my view. In an ever-expanding universe of cultural niches, new ones explode into being every minute, and no one can keep track of them all. True weirdness can’t be perceived by outsiders, only by the weird themselves. I’m no Dune scholar, but the “weirding way” of its Bene Gesserit cult seems dead-on: a martial art that grants practitioners superhuman speed and precision — to us onlookers, they transcend time and space in a way our brains can’t process. Between us and them (or them and us?), there remains a gulf of unknowability. The weird belong to both the past and the future, ungraspable in the here-and-now.

Still, there is one way to be truly weird, in the pejorative sense. And that’s not to know that you’re weird. This is what Kamala Harris and Tim Walz zeroed in back in 2024, when they pegged J.D. Vance and his ilk as “weird” — not in the Austin/Portland way but in the sense that those far-right Republicans truly think their bizarre ideas and habits and dreams represent a broad mainstream of America. This seemed like such an effective attack, because those Republicans had no self-consciousness. They were incapable of seeing outside of their own warped and insular world. They couldn’t defend themselves, because they could never laugh at themselves. God, they were so weird!

And they were so weird in part because they didn’t realize that we’re all weirdos. We all have disgusting bodies that will fail sooner or later. We all screw up and say the wrong thing. (Bless your heart!) We all get sidetracked and captivated by our own little obsessions that almost no one outside of our loved ones and a dozen strangers across the Internet understands and shares. The difference is that most of us accept our weirdness, and laugh at it, and decide never to give a damn if our hairstyles look funny, if our music is off-putting, if the love and acceptance we extend to friends and strangers is reciprocated or even acknowledged. We weirdos are always just going to be ourselves, whether our rockets are hot or not. 🪨🪨🪨