“Calf’s Head and Ox Tongue” (c. 1882), Gustave Caillebotte

Today’s advertiser is our old friend, Authory. Beehiiv rules prevent me from asking or encouraging you to click the ad, but if you do so, of your own free will and according to your own moral principles, each click will earn me $2.40.

Approximately 40 years ago, I was browsing the basement level of the Jeffrey Amherst Bookstore when a thin volume in the humor section caught my eye. Bred Any Good Rooks Lately? was the questionable title, and it promised just over 100 pages of “puns, shaggy dogs, spoonerisms, feghoots & malappropriate stories” by writers such as Stephen King, Peter Straub, and Madeleine L’Engle (whom I’d heard of), Annie Dillard, Roy Blount Jr., Mark Strand, and Donald Hall (whom I hadn't), and a dozen other writers no one has thought about in decades. I chuckled at the title, forked over $4.95 of my allowance, and opened it as soon as I got home. What I found within has stuck with me ever since.

Well, parts of it. Each of its twenty or so chapters is a very brief story or poem designed solely to set up the punning punch line. What was the titular tale about? Who cares? “Bred any good rooks lately?” was its raison d’être. As were “The koala tea of mercy is not strained,” “It’s a wrong, wrong lay to rip a terry,” and “The Moron Tab and Apple Choir.” Those I’m pulling straight from memory, though I have the book—which has sat, unread, on a shelf in the downstairs bathroom of my parents’ house for more than a decade—at my side right now. Each feghoot (that’s the best definition) exists as a demonstration not just of its creator’s wit, so to speak, but of their facility with the language, their ability to catapult hoary refrains into fantastical territory. “You can’t teach an old trog new dicks.” “What’s a nice pearl like you doing in a glace like this?” “With Franz like this, who needs anemones?”

The book attuned 12-year-old me to linguistic slipperiness in a brand new way: Words, these vital units of human communication, were only barely holding on to their meanings! A flip-flop of consonants, the intrusion of a false cognate (un faux ami!), a prosaic mondegreen—any of those could at any instant nudge the crazy train that is English off its rails and send it careering (or is it careening?) into the abyss. The fact that we somehow manage to convey any information to one another at all seemed like dumb luck at best. And the precariousness of the situation might have freaked me out, except that it was so damn fun. At this same time, I was discovering Monty Python, and I was learning French, and getting involved in a subculture, skateboarding, that had its own fluid, fast-evolving lingo. For the first time, I think, I was beginning to feel in control of the idea of language—apart from it, outside of it in some ways, able to see its potential and its weaknesses—and to play with it, to the delight and surely exasperation of my friends and family.

And in the decades since, this feeling has only deepened, though it has taken some unexpected turns.

More after the ad…

🪨

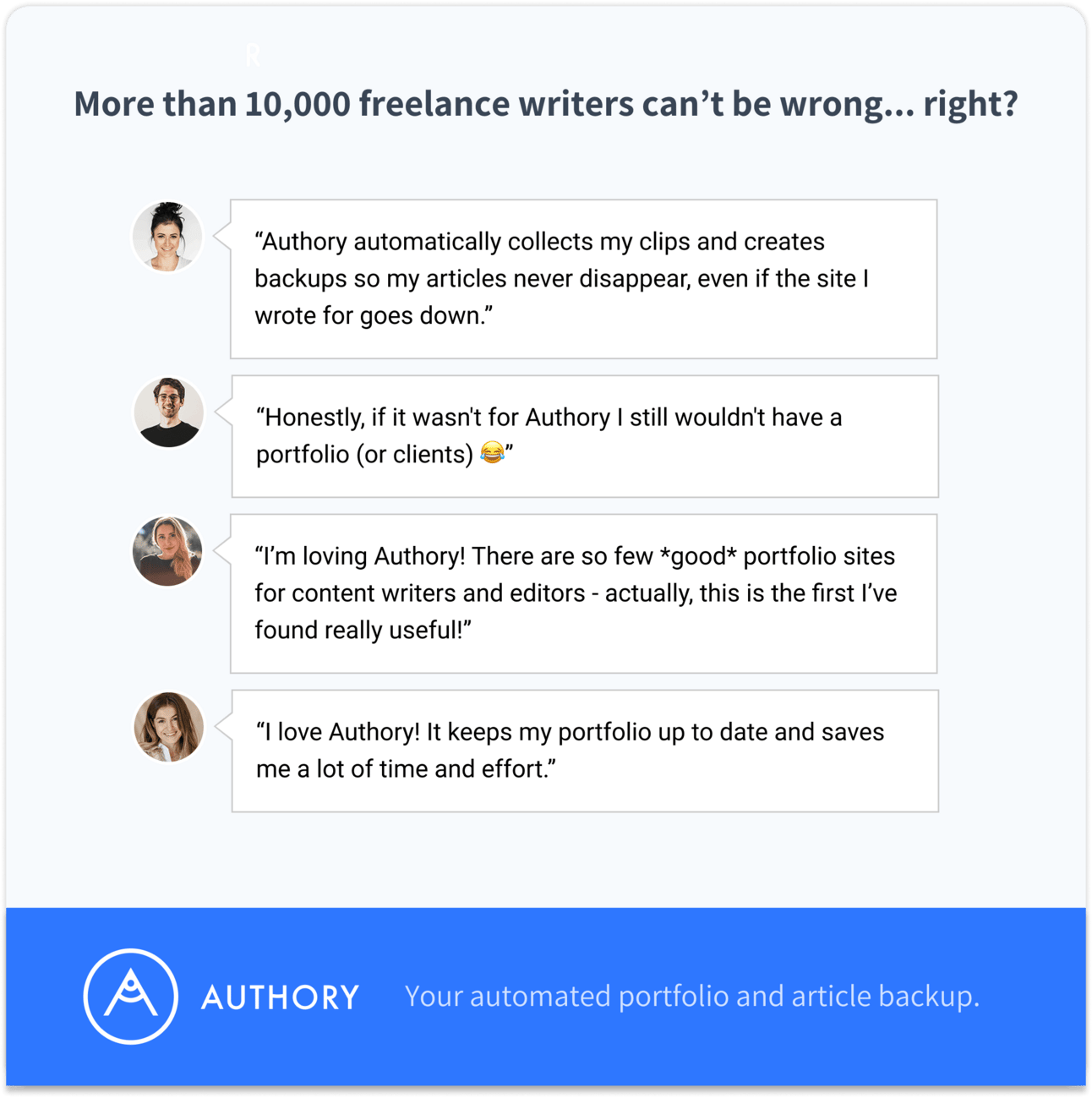

Finally, a portfolio that's auto-updating, and creates backups of your work.

If you're a writer, journalist or content marketer, you are probably familiar with these struggles:

Spending hours updating your portfolio page to keep it fresh.

Losing your work samples due to site shutdowns.

The good news? Authory has you covered.

It automatically pulls in your content and creates a stunning portfolio that updates itself every time you publish.

Plus, it backs up all your work, so you never have to worry about losing anything.

Ready to impress potential clients and employers?

🪨

I would love to say that I live in a bilingual home. My wife, Jean, grew up speaking Mandarin Chinese, my first language is English, and under different circumstances, our two daughters would speak both more or less perfectly, and my Chinese would be good. But that is not the case.

My Chinese is bad and will never be good; Jean’s English is essentially that of a native speaker, with tiny but revealing tics that all but the most attentive listeners will miss. Of the kids, the older one speaks Chinese better than the younger, and cares more about improving her abilities. She’s also studying French in high school, and getting excellent grades, though she’s reluctant to say un seul mot aloud in front of us, her parents, who also speak French (me better than Jean). Our younger daughter has also spent time on Duolingo learning Italian—which I speak with enthusiasm, if not expertise—and should probably really study it in high school.

So what does that make us? Quadrilingual? Wait, let’s make it even messier. We often say “Itadakimasu!” when we sit down to dinner. (Jean studied Japanese and German in high school.) “하지마!” became a running joke at home when our sassy younger daughter blurted it randomly when she was 4 or 5. I greet my co-workers on Slack with “Guten morgen” or “Bom dia!” I embarrass everyone by ordering in Vietnamese at Vietnamese restaurants.

Look inside my head, though, and the babble becomes even more deafening. Thanks to a couple of decades of travel, I have fragments of Turkish, Indonesian, Thai, and Khmer rattling around my skull. (In Cambodia, when someone asks how you’re doing, you can say “Sok sabai,” meaning happy-healthy, or good, but you can also say “Sok sabai, sai sabok,” which doesn’t mean anything extra—it’s just juggling the sounds for fun!) Under my breath when I’m alone, I silently practice pronouncing the Czech ř and the Polish ł, though I can’t speak a word of either language. I’ve learned to read Spanish ads on the subway (“Abajo con el azúcar de su sangre, arriba con su vida!”), and I can at least sound out Cyrillic and hunt familiar cognates. In Danish, I can almost ask for a hot dog with bread. In Cantonese, I can say, “Thank you, fuckface.”

Is this normal or unusual? I don’t know how other families operate or how even my closest friends, most of them supremely well-traveled, think. I do know that when I was writing travel stories for large publications, editors cautioned me against admitting I spoke or understood other languages, even if casually and imperfectly. (This one was an exception.) It seemed to read to them as show-offy and self-congratulatory, like those polyglots who make the smallest of small talk in 25 tongues on YouTube. So I assumed that my own multilingual experience was rare and unrelatable. But maybe it isn’t?

Yet I’d hardly call myself or our family “polyglot.” Only Jean2 is truly bilingual. For the rest of us, and especially me, it’s just English, albeit an English barnacled with so many loan words and imported parentheticals that it would be unrecognizable to anyone who didn’t have precisely the same vocabulary and set of cultural references1. The kids may one day master Chinese, or French, or Italian, but I doubt I’ll ever speak another language like a native, or even close. With French I came close, and I’d love to improve my Italian, but these days it’s impossible to find the time not just to study but to travel, or even live, in France or Italy. Maybe when I retire, if my brain is up to the challenge, I’ll see if I can make some progress. But until then I’ll have to continue living not in multiple languages but amid them, catching meaning and making meaning as I’m able, and meanwhile enjoying the slippery miracle that is language itself.

Frankly, English is not the worst language to be handcuffed to. I’m not talking about its status as an international lingua franca—I’m thinking more of how flexible it is. We have rules, sure, but those can and are bent into shapes that should be recognizable but somehow aren’t. Our spelling, fucked up as it is, lets us warp and twist our writing to convey accents and intonations that more rigidly constructed languages might not so easily permit. English is above all a forgiving language: A new speaker can mispronounce, use the wrong tense, and deploy an alien cadence, and we’ll still figure out what they mean, and probably just assume they’re from backwoods Mississippi or Louisiana. (By contrast, the wrong tone in Chinese makes you unintelligible, and few French have patience for imperfection.) And because English is so forgiving, it’s also assimilationist: Any foreign word can become English, no questions asked, although its pronunciation may be radically transformed, and even new linguistic structures can be grafted on with little confusion. In London, kids are saying “I went chicken shop” rather than “I went to the chicken shop.” In Miami, thanks to Spanish, “get down from the car” is replacing “get out of the car.” No one’s in control, and we all love it.

And this ain’t exactly new: English was always made of foreign tongues, Anglo-Saxon West Germanic getting a hefty dose of quasi-French with the Norman invasion, plus eventually some Latin and Greek thrown in to muck up our spelling. When people and cultures collide, rules get thrown out and whatever works, well, works.

In that sense, you could see the languages we speak at home, and that I speak in my head, not as many languages but as one: an English from the far future, as Khmer as it is Korean, inflected with Italian, rife with Chinese. Stick me in a time machine and send me to the year 2525, and the toxic mutants who are our distant descendants will understand me as one of their own. Alas, no time machine. I’m trapped here in the past with you, and you with me, engulfed in a fog of phrases and phonemes that mystify, amuse, and enlighten, sometimes simultaneously. As the poet Tom Clark once wrote, “It’s all mist for the grill!” 🪨🪨🪨

It’s Good and I Like It: The Cut is into striped shirts, too

Striped shirts are the best, and although I was not interviewed for this story in The Cut, I do approve of their selections.

Read a Previous Attempt: The most important travel story ever

1 I considered writing this piece using every language I know, but come on: That’s ridiculous.

2 Jean Liu married a lean Jew!