Today’s advertiser is Contrarian Thinking. Although Beehiiv rules forbid me from asking or encouraging you to click the ad, if you do so, of your own free will and according to your own moral principles, each click will earn me $2.37.

In 1973, a screaming came across the sky. It had happened before, but there was nothing before to compare it to. Now, however, more than 50 years after the publication of Gravity’s Rainbow, Thomas Pynchon’s masterpiece of style and paranoia1, it’s time to make some comparisons.

The first time I read Pynchon, I got perhaps 40 pages into The Crying of Lot 49 (1965) before I realized I did not understand a damn thing. This was during college, in the early 1990s, and I’d been told — I can’t remember by whom — that if I wanted to be a writer, I needed to read Pynchon. Even then, Pynchon’s legend preceded him: He refused to be photographed or interviewed or to do any sort of publicity for his novels, whether because he was ashamed of his buck teeth or because he wanted to be judged on the quality of the work alone. He was an enigma who wrote about the enigmas lurking at the edges of contemporary life, above us and below us, directing our destinies but invisible — unless we had the curiosity and/or paranoia to see them clearly. I loved that kind of shit as a young man, so I tried to read him.

And I couldn’t. There was something about the rhythm of the sentences, the leaps in time and place and tone, the unwillingness to step back and explain what the hell was going on that threw me off. Here’s the second and third page of the book, just after our heroine, Mrs. Oedipa Maas, has been informed that an old boyfriend, Pierce Inverarity, has died, and that she is to be the executrix of his estate:

Through the rest of the afternoon, through her trip to the market in downtown Kinneret-Among-The-Pines to buy ricotta and listen to the Muzak (today she came through the bead-curtained entrance around bar 4 of the Fort Wayne Settecento Ensemble’s variorum recording of the Vivaldi Kazoo Concerto, Boyd Beaver, soloist); then through the sunned gathering of her marjoram and sweet basil from the herb garden, reading of book reviews in the latest Scientific American, into the layering of a lasagna, garlicking of a bread, tearing up of romaine leaves, eventually, oven on, into the mixing of the twilight’s whiskey sours against the arrival of her husband, Wendell (“Mucho”) Maas from work, she wondered, wondered, shuffling back through a fat deckful of days which seemed (wouldn’t she be the first to admit it?) more or less identical, or all pointing the same way subtly like a conjurer’s deck, any odd one readily clear to a trained eye.

One sentence! Whew! After struggling through a few dozen pages like that, I put the book down, not at all sure what I’d even been through up to that point. Maybe Pynchon wasn’t for me?

But then, a few weeks later, annoyed at having failed the challenge, I picked it up again. Lot 49 was only 172 pages, barely a quarter of Gravity’s Rainbow. Surely I could tough it out. And so I did. And in that second attempt, something clicked. The asides and interruptions, the kazoo obsessions and silly names, the bourgeois attention to homemaking and the constant undercurrent of fate — they all began to make sense. I found a way to ride those wild sentences wherever they happened to be going, and to observe the story along the way: the kooky side characters, the deepening conspiracy, and the plight of the relative normie (relative being a relative term) who protagonized their way through it. Amid all the dazzle and the silliness, I could feel something, the alternating modes of connection and alienation that ruled Pynchon’s world, his world being our world, too. Dammit, I liked this writer!

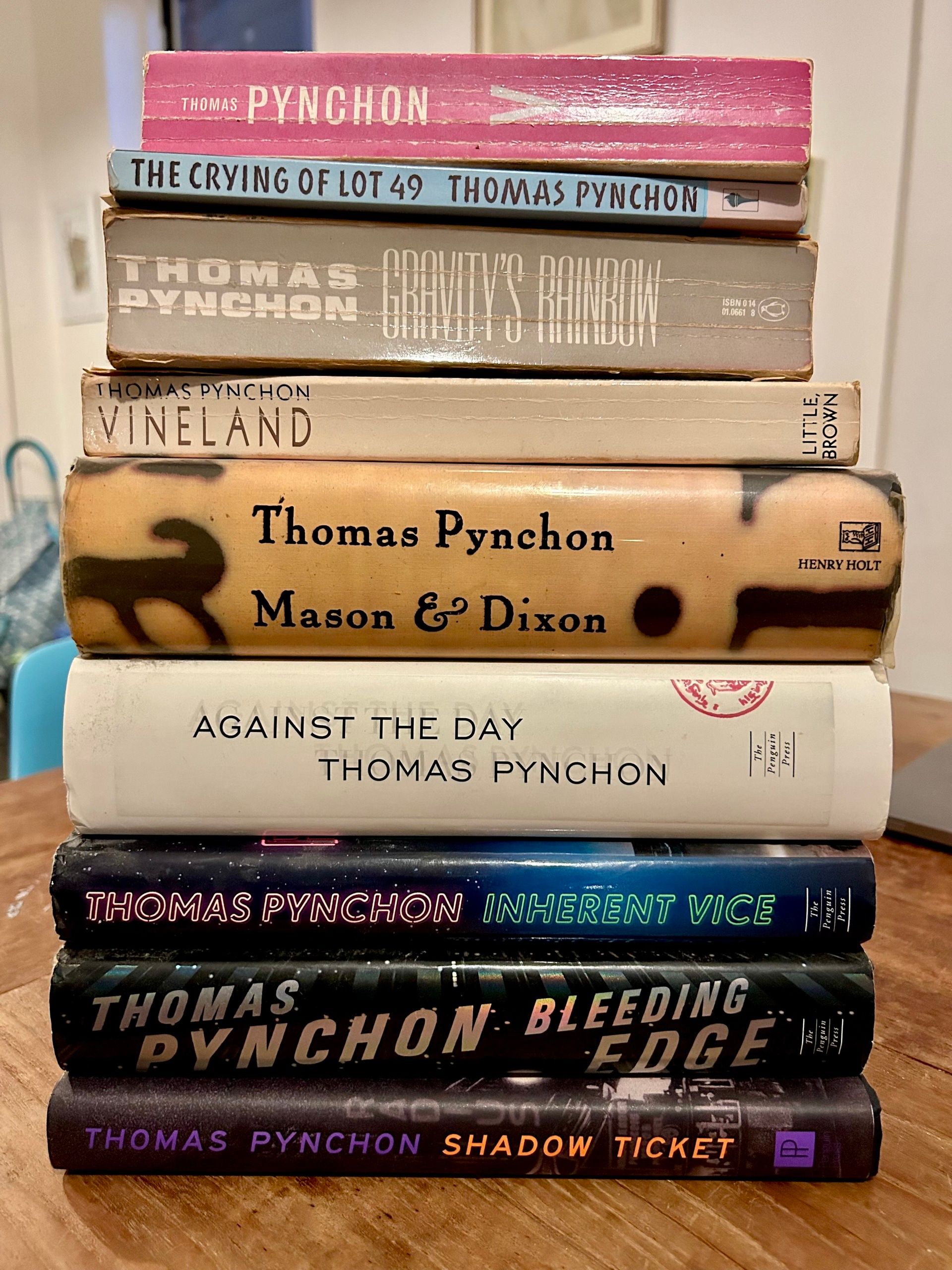

My collection, I guess.

Gradually, I made my way through Pynchon’s other works, of which there were few: V., his first novel, published in 1963; Slow Learner, a collection of his early short stories; Gravity’s Rainbow; and Vineland, a 1990 novel that reviewers, who’d been waiting 17 years for this next book, seemed to consider Pynchon Lite. Each challenged me in the same way as Lot 49. The sentences threw me off, and after 40 pages or so I’d give up, until, after a breather, I’d come back to discover I could relax into the Pynchon universe. Each book remixed a similar set of stories, styles, and themes, as its characters navigated a world ruled by unseen forces — political, economic, scientific, mystical, even postal — discovering how little power they themselves possessed, but also how they could live satisfying lives beyond the reach of history. There would be goofy songs (“Just a floo-zy with-an U-Uzi … / Just a girlie, with-a-gun”), elaborate set pieces (a banana party, a nose job), a dash of thermodynamics, and appearances by impossible populations of the passed-over (the dead-but-not Thanatoids, the suicidal Hereros). And always, always those uncompromising, ecstatic roller-coaster sentences, crafted clearly for Pynchon’s own pleasure but also, then, of course, for ours.

Here’s Gravity’s Rainbow’s Tyrone Slothrop chasing his lost harmonica down a toilet into the sewer pipes:

The light down here is dark gray and rather faint. For some time he has been aware of shit, elaborately crusted along the sides of this ceramic (or by now, iron) tunnel he’s in: shit nothing can flush away, mixed with hardware minerals into a deliberate brown barnacling of his route, patterns thick with meaning, Burma-Shave signs of the toilet world, icky and sticky, cryptic and glyphic, these shapes loom and pass smoothly as he continues on down th along cloudy waste line, the sounds of “Cherokee” still pulsing very dimly above, playing him to the sea.

Here’s Vineland’s Frenesi getting nostalgic:

Frenesi’s tears would slow and dry, her postpartum lust for death would cool, she would on a day not far off actually find herself liking this infant with the offbeat sense of humor, and she and Sasha would take up, not as before, but maybe no worse than before.

And Oedipa Maas, having learned too much but not enough, in the full grip of paranoia:

Old fillings in her teeth began to bother her. She would spend nights staring at a ceiling lit by the pink glow of San Narciso’s sky. Other nights she could sleep for eighteen drugged hours and wake, enervated, hardly able to stand. In conferences with the keen, fast-talking old man who was new counsel for the estate her attention span could often be measured in seconds, and she laughed nervously more than she spoke. Waves of nausea, lasting five to ten minutes, would strike her at random, cause her deep misery, then vanish as if they had never been.

Over the decades, I’ve read these sentences and these stories enough times that I can now dip in and dip out, sampling them till I get drowsy, knowing that even if I’m only getting part of the whole big-ass tale, that’s how it is anyway, right, beginnings and endings just constructs we put up with to enjoy the burger-juicy middle.

More after the ad…

🪨

Learn Business Buying & Scaling In 3 Days

NOVEMBER 2-4 | AUSTIN, TX

“Almost no one in the history of the Forbes list has gotten there with a salary. You get rich by owning things.” –Sam Altman

At Main Street Over Wall Street 2025, you’ll learn the exact playbook we’ve used to help thousands of “normal” people find, fund, negotiate, and buy profitable businesses that cash flow.

Tactical business buying training and clarity

Relationships with business owners, investors, and skilled operators

Billionaire mental frameworks for unlocking capital and taking calculated risk

The best event parties you’ve ever been to

Use code BHP500 to save $500 on your ticket today (this event WILL sell out).

Click here to get your ticket, see the speaker list, schedule, and more.

🪨

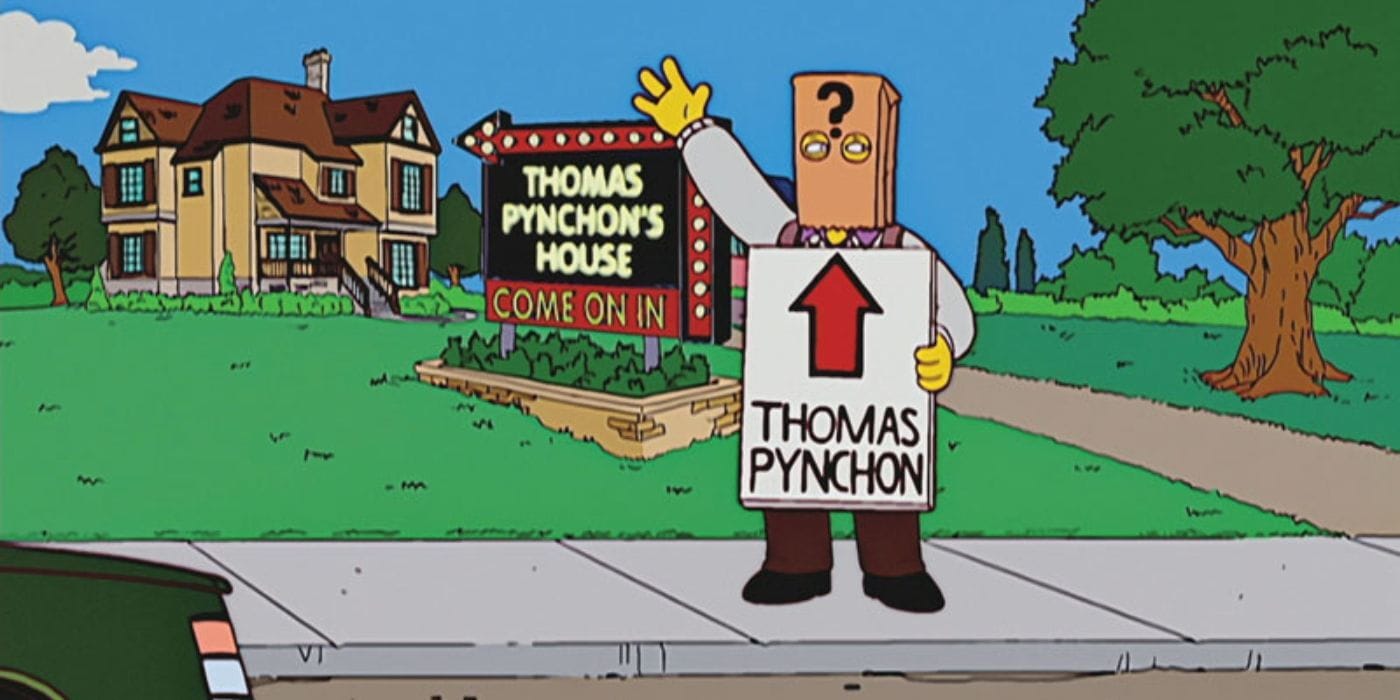

In the last 30 years, Pynchon has gone from celebrated but obscure to enormously celebrated and slightly less obscure. Where he used to publish so rarely that his fans sought evidence of his existence in Letters to the Editor he may or may not have written, under a bag-lady pseudonym, to a small California newspaper, he’s now put out five novels since 1997: Mason & Dixon, Against the Day, Inherent Vice, Bleeding Edge, and the just-released Shadow Ticket. Though he has maintained his aura of secrecy, he’s also managed to live a public life, writing liner notes for bands he likes, “appearing” on The Simpsons, and existing in New York City in a trackable way, if you care to track him. His literary reputation and cultural influence have only grown, while his brand of paranoia and his obsessions (pop culture, science, the shadows of history) have become mainstream America’s. The best movie of 2025, One Battle After Another, is a loose adaptation of Vineland, and it is so, so good. You should see it.

You don’t, however, have to read Shadow Ticket. Because it is not good.

This is unfortunate to have to say, because I’ve spent so much of my life reading — and enjoying reading, and trying to figure out how to be influenced by — Thomas Pynchon. I like him (the Authorial Him, anyway) and his writing, and his worldview makes sense to me, this unsolvable struggle between shadowy powers and us relative normies. I’m oddly proud of his stature, but maybe that’s just the attitude of any fan who was a fan back in the day, before the band hit it big. But as a fan, as someone who likes to think he really got the early work, I have to come out and acknowledge that this new work isn’t working.

(And maybe it’s not just the new book but the last few of them, too. I know I don’t recall the characters and set pieces of Bleeding Edge or Against the Day the same way I can the minor moments and side quests of Lot 49. But I don’t quite have the energy to go digging for badness in the recent oeuvre, so there you go.)

Shadow Ticket seems like it should work. Set in the early 1930s, it’s got plenty of potential Pynchoniana: Hicks McTaggart, a burly Milwaukee strike breaker turned private eye, is convinced, cajoled, and otherwise coerced into tracking down a missing cheese heiress, also a missing mythical Austro-Hungarian submarine, also also a hideous lamp that has a habit of disappearing into thin air. Never quite knowing who he’s working for, and who might be working against him, Hicks finds himself driven ever farther east, across the Atlantic, to Vienna, Budapest, and beyond, encountering spies, playboys, dames, gangsters, Nazis, and more spies. Nice setup, eh?

The problems are twofold, and I think mixed up with each other. The first is the sentences, which are the same as ever… yet not. The interruptions, the digressions amid digressions, the litany of gerunds — they all feel more mannered than before. Here’s the backstory, for example, of Hicks and his girl, April:

They met at the Aragon Ballroom in Chicago, near the el, half a clam to get in, cork, felt, and spring-cushioned floor, palm trees, archways, tile, the Spanish palace courtyard treatment, secret tunnel to nearby Capone hangout The Green Mill, only white people allowed in.

Or Hicks realizing he doesn’t need to bash heads in:

Hicks was slowly becoming aware at this time of what you could call a change in outlook, finding himself mysteriously in and out of the Toy Building down on 2nd Street or Nan King, a new south side joint, places that specialized in chop suey and dancing, not his usual idea of a Saturday night, and on another unexpected weekend in Chicago actually required to mediate, without understanding a word of Chinese, between On Leongs and Hip Sings regarding their uneasy arrangements about who’s supposed to get the opium trade and who the needle drugs such as cocaine, also receiving on top of a tidy fee from both parties a number of chain mail undershirts which turn out to be useful when wandering into moments of Chicago street recreation…

Or Hicks, stuck in New York City and hoping to go home:

He goes to a Western Union office and wires Milwaukee—60¢, means he’ll have to skip lunch, YOU CRAZY NO DICE WIRE FARE HOME SOONEST, leaving him two words under the limit, the two words that come to mind not being allowed, and stranded on the “beach” in front of the Palace Theatre along with jugglers, ventriloquists with dummies, ukulele virtuosos, casualties of acts no longer sure, in these final days of vaudeville, of being hired anywhere, not even along the death trail stretching southwest through farm towns, broken country, and deserts toward L.A. like a panhandler’s arm seeking the tiniest handout of mercy from the source of its sorrows.

Is it just me, or do these sentences feel directionless? Could they not be split in two or three and retain their meaning, their import, their finesse? What’s gained by these agglomerated clauses? Instead, the sentences start, they build, and then they meander, not off on lines directed by forgotten Rosicrucians or the dictates of quantum mechanics but, well, nowhere in particular. And so they rarely arrive.

Likewise the story itself. It cannot stand still. For every scene we get centered on Hicks, we get two more revolving around some kooky character he meets — who may vanish a few pages later, never to reappear. Their backstories take up a goodly amount of the book’s scant 293 pages, meaning that when the main story moves forward, it happens in jolts and jumps. Around 120 pages in, Hicks leaves Chicago on a train headed east, through Pittsburgh, to New York, onto a transatlantic steamer, and by the time 30 pages have gone by is passing through Belgrade — having met a dozen or more (in?)consequential characters in the interim. At this pace, with a tale that interrupts itself reflexively, Hicks and whatever he deep within himself is seeking vanish into the background. With Pynchon’s attention span measured in seconds, it’s hard to care about any of it at all.

I would like to believe this is intentional. Gravity’s Rainbow made a point of the dissolution of its main character, Tyrone Slothrop, who doesn’t even really make an appearance in the final 50 pages. But that book luxuriated in its asides, following the sewer lines as far down as they would go, because it knew they’d all wind up connected, if only sometimes metaphorically and maybe beyond our mortal view. I wish I could say Shadow Ticket feels like Pynchon streamlined — breezy and deft — but instead it’s Pynchon performing Pynchon, or, worse and more concerning, Pynchon trying to recall what he used to be able to do, and managing only the superficial act.

After 195 pages, well past my usual 40, I stopped reading, and I feel no need to continue.

It is a strange thing to watch a writer you love, or loved, age. When you first fall in love with them, you want as much as possible — more than they have given the publishing world so far. But when your adult life winds up dovetailing with the bulk of their career, you get to observe the changes, for better or worse. You hope each new work will provide something like the thrills of the established oeuvre, but also carry it forward in some surprising but also inevitable new way. Sure, okay, there may be missteps, lesser works, thin ideas an overambitious publisher should have said no to. But on the level of style, of the most basic approach to building sentences, paragraphs, scenes, chapters, you hope or even assume consistent progress: an excellent writer should only become more so, right? And their sense of story, of what amounts to a satisfying arc, should fare the same, perhaps with quirks, obsessions, and experiments, but also refinement and confidence. Sixty-plus years of fictioning gotta amount to something!

It’s pointless, I think, to speculate on real-world reasons for Shadow Ticket’s failure. The one thing Pynchon himself has been clear on since before the Vietnam War is that the work is the work and should be judged apart from anything we might know of its author. And so I won’t, except to acknowledge the guy is now pretty old, and we might not see too many more novels bearing his name. I hope we do — I hope we get another Lot 49 or Gravity’s Rainbow — but I’ll understand if we don’t. Writing is hard.

Instead, I’ll content myself with how successfully the Pynchonian worldview I once fell in love with has captured pop culture — nowhere more than in One Battle After Another, directed by Paul Thomas Anderson. Like Vineland, it’s about a man, a former revolutionary (played here by Leonardo DiCaprio), who has raised his teenage daughter in hiding from the law and who, when discovered by The Man, must go on the run and contend with the legacy of the wife who betrayed him. There are Christmas-loving white-supremacist cabals (“Hail Santa!”), nitpicking underground help lines, old cars, new cars, stoner nuns, uncomfortably comical boners, ass-kicking women, and a kick-ass soundtrack — it’s as Pynchonian as movies ever get2. And it’s most Pynchonian in its outlook and resolution: The Powers That Be will continue to Be, and the fascists will more or less win, but We the People won’t exactly lose, either. Instead, whenever we’re not being chased or caged or beaten or murdered or oppressed in lesser but no less painful ways, we’ll all find the means to take care of one another, leaping from rooftop to rooftop like teenagers, sassing the authorities, enjoying a beer and a joke and a song and a fuck because in the next moment, or in the digression after that, we might get wiped from the page. But until then, no matter how minor our characters happen to be, we get to live. 🪨🪨🪨

1 Whose opening lines I’ve vandalized here.

2 And way less annoying than Paul Thomas Anderson’s take on Inherent Vice.