“Kitchen Scene” (1620), Peter Wtewael

The first thing I noticed about Condé Nast was all the high heels. They were everywhere: clicking through the lobby of 4 Times Square, pacing through the hallways, shiny, tall, hard. These women going to work at Vogue and Glamour and Vanity Fair and The New Yorker took their outfits seriously. It was October 2012. I had spent the past eight years freelancing from my apartment in Brooklyn (not to mention traveling around the world for the New York Times, Saveur, and Afar), and I’d forgotten that this Manhattan world of put-together professionals was real, and not just a Devil Wears Prada myth.

And now I was supposed to be one of them.

I had been hired as the editor of BonAppetit.com, my first full-time job since late 2004, when I’d left New York Magazine. BonApp was not a publication I’d given much thought to before I applied for the gig. In the Condé Nast stable, it had always been overshadowed by Gourmet, the beloved food magazine that had been closed down by its owners in 2009. In the broader media world, Saveur commanded more of my attention—I appreciated its nerdy enthusiasm for long-form features on the farther-flung cuisines of the world. (That’s why I wrote for it!) And Food & Wine, then owned by American Express, still had a high-budget sheen of glamour. (I wanted to write for it!) Bon Appétit, which had launched in 1956, had always been less chic, more traditional. “In the early years,” the Wall Street Journal wrote, “its focus was simple, easy recipes that taught the average American housewife how to upscale her cooking.“

But after the shuttering of Gourmet, change was afoot. In 2010, Condé Nast moved BA from L.A. to New York and installed GQ’s style editor, Adam Rapoport, as the new editor-in-chief, and over the next decade he would oversee the publication’s rise to food-culture dominance—and its ensuing fall amid scandal and recrimination. Five years after that precipitous moment, I wanted to take a look back at the time I spent at 4 Times Square, partly because there’s a lot of Condé Nast nostalgia in the air right now, with everyone recalling the glory days of the high-end magazine world, but also because I’ve never written about this myself and, um, I guess I just feel like it?

So, here goes: a recap of the events of fall 2012 to fall 2014, from my particular point of view. No doubt I’ve forgotten a ton while misremembering everything else, but that’s how these things go, people.

Wolf-boy seeks job, wolf-boy gets job

When my wife, Jean, got pregnant with our second child, I figured I should find a real job. Up till then, I’d been a freelance travel writer, often away from home for two weeks or more at a stretch, and that no longer seemed fair to Jean. So in the summer of 2012 I wrote an email to a couple hundred friends with the subject line “Wolf-boy seeks job.” One of them forwarded me an email looking for an online editor for Bon Appétit, and I applied. Fairly quickly, they called me in for interviews, so I hustled to try to understand what the new BA was about.

Actually, before I get to that, I need you to understand what the food-media world was like in the first decade of the twenty-first century. It was, well, very female. Ruth Reichl ran Gourmet after a stint as the Times’ best restaurant critic; Barbara Fairchild headed up Bon Appétit; Dana Cowin was EIC at Food & Wine; and Martha Stewart’s aesthetics dominated American home cooking. Men were not absent, of course. You had Adam Platt as the critic at New York, James Oseland atop at Saveur, and Anthony Bourdain making the transition to travel personality. And male chefs were obviously still running the vast majority of restaurants. But at home—the realm of magazines, recipes, and meal prep—men were invisible.

That started to change in the latter half of the decade. Dadbloggers began to saturate the Internet, offering new perspectives on parenthood and new openness, even enthusiasm for the household tasks that, in generations past, had been women’s burdens by default. In 2011, Hachette published Man With a Pan, an anthology of essays by Mark Bittman, Stephen King, Jack Hitt, Shankar Vedantam, and Jim Harrison about, you know, being a dad and cooking. (I reviewed it for Saveur.) Maybe this wasn’t revolutionary, and it certainly didn’t stop men everywhere from just being terrible pieces of shit, but it felt like a small step toward something better, or at least different.

In that light, Adam Rapoport’s hiring made a lot of sense. For as much as he was quoted on the intersection of food and style and celebrity, he also talked about the joy of cooking for his family. It may sound crazy in 2025, but the idea that you could be a well-dressed, culturally involved man who not only wanted to make dinner but also eat it with his wife and kids, and maybe even clean up afterward—that was new!

And it wasn’t just new, it was me (minus the well-dressed part). So this seemed like a direction I could get with, and expand upon. In a couple of interviews, first with the special projects editor and the managing editor, then with Rapo himself, and then in an edit memo, I explained that I wanted to find the food angle in everything: music, movies, art, politics, science—anything and everything, enormous and minute, in our human American lives. And on the Internet, where there were no limits, we’d find a receptive audience.

So they hired me.

Cheese cheese cheese cheese cheese cheese cheese cheese cheese

Bon Appétit occupied maybe half a floor at 4 Times Square: There were cubicles, a library and archive, and lots of actual offices. Rapo’s was at one end of the building, and was big, with enormous windows, a well-stocked bar, multiple sofas, and his own private bathroom. Mine was at the other end and windowless, but with a door that not only closed but locked and, eventually, a cheap bar cart stocked with giveaway bottles and a $99 convertible couch that an art-department colleague told me was known as a “flip-and-fuck.” Even better, I had a solid salary and—imagine this in 2025!—an $8,000 annual expense account. Now that I think about it, maybe I should’ve bought a nicer couch.

Surrounding me, some in cubes, others in shared offices, were my digital team: two editors, two producers, a writer, and a few others who divided their time between the web and print. (No one wore high heels.) I like to think we came together pretty quickly, thanks in part to Superstorm Sandy, which drowned New York about a week or so into my tenure. The disaster gave us a chance to find those food angles: how to get your kitchen ready for a hurricane, what our Twitter followers cooked during the storm, what we cooked after the storm, how restaurateurs were recovering. It was fast and friendly, and it was of a piece with BA in that era: Here were the food-obsessed folks at the magazine/website sharing their obsessions with the world. Unlike other publications, we didn’t need to constantly lean on chefs for expert advice (though we frequently spoke with them), because we knew a fair bit ourselves—and we had a sense that our readers, as young and food-obsessed as we were, would listen to us.

From there on out, things were easy and fairly fun. Our search for food angles led to pieces like The History of the Car Cup Holder, which ran on Presidents Day because you know how there’s always car sales on Presidents Day weekend? Well, that was enough of a hook for us. We published an oral history of Attack of the Killer Tomatoes because it was August, hence tomato season. We taste-tested peanut-butter cups and listed hot sauces from all 50 states. I wrote about every drink in every new episode of Mad Men. Instead of following the “common mistakes” trend, we’d publish an enthusiastic How to Throw the Worst Dinner Party of All Time—or Not! (Enthusiasm, I learned, was key to making stories work: Never be negative was my rule.) At the height of the mania for the Carly Rae Jepsen song “Call Me Maybe,” we ran a story on cake-ball pops with the headline “Ball Me, Maybe?” We named one recipe slideshow “24 Chicken Breast Recipes That Are NOT BORING.” My favorite headline was this one: “Cheese Cheese Cheese Cheese Cheese Cheese Cheese Cheese Cheese.” I don’t remember what the article was about, but I think it might have been cheese.

When you’re taking this kind of wide-ranging editorial approach, it helps to have reliable, inventive writers at your disposal, and I had some of the best. Over my two years, our staff writers included Sam Dean, Chris Michel, Dan Piepenbring, and Rochelle Bilow, all of whom were geniuses, able to write not just about food but about etymology, Superman, the zombie apocalypse, holiday playlists, government shutdowns, and The Goonies. That’s not to mention the other digital editors—Julia Bainbridge, Danielle Walsh, Carey Polis—who shaped the project, plus our producers, Erik Peterson and Melissa Finkelstein, various members of the print team1, photographer Alex Lau, and a ton of freelance contributors, including the photographers Dylan + Jeni, who we sent to shoot the food at strip clubs in Portland, Oregon (NSFW). Our budget was small, but we used it wisely.

The insane thing is this: It all worked! We saw traffic rise from 1.8 million monthly page views past 2 million, then 3 million, and eventually past 5 million. (We had team parties at each milestone.) People followed us on Twitter, on Facebook, on Instagram. We’d made a bet, and it was paying off.

And yet we were still relatively tiny. Epicurious, our corporate sibling, had ten times our traffic, maybe twenty. I’m sure Food & Wine’s website dwarfed ours, especially after they sold to Time, Inc. We could do all the weird stuff we did because, in those early days, nobody was paying attention, we had little status or power, and we had nothing to lose.

Also, we didn’t know what we were doing. The SEO concerns that would come to rule food websites were mostly afterthoughts. For a long time, we didn’t pay real attention to social media. There was an email newsletter, and it generated traffic, but we never considered its potential. We ran occasional videos on the site, often sponsored by car companies, and literally no one ever watched them. Imagine this: Bon Appétit had no YouTube presence.

(We did eventually learn a thing or two. We started adding the word “Recipe” to the title tags of our recipes. We thought, What if we posted more often on Facebook and wrote in a fun voice on Twitter? We figured out that most readers had never heard of our favorite restaurant chefs, so even Daniel Boulud became known as “New York City’s best French chef.”)

In general, we worked in a bubble: Brainstorm crazy ideas at a daily 10 a.m. standup, write and publish them over the next several hours, see how it went, and go home before 6 p.m. Stacey Rivera, the managing editor, referred to us as “the island of misfit toys” in the ocean of drama and dysfunction that was, presumably, the rest of Condé Nast. I may be succumbing to nostalgia in my old age, but I think it might have been true, especially of the digital team. Because when I looked beyond our nook to the rest of BA, it was a different world. Yes, the magazine presented an image of gorgeous (but real!) staffers eating, drinking, cooking, and having an amazingly good fucking time. And I’m sure they did. But the print team also stayed late, often till 8 or 9 p.m., often (I heard) hastily rearranging spreads according to new whims. (Sadly normal for the magazine world.) Once, when I was visiting the test kitchen a floor below ours, one of my favorite test cooks burst into tears in front of me, stressed beyond her limits by the demands placed upon her. Were these glimpses of the “traumatic environment” people would describe in the years to come?

What’s sexier?

A lot of you may be reading this piece to learn more about Adam Rapoport, either new dirt or exculpatory evidence. Well, here you go—this is your section! But prepare to be disappointed. Because Adam and I didn’t interact all that much.

Mostly, I took this as a good sign. If traffic was growing and the IG was hot, what was there to talk about? He had a print magazine to put together, VIP dinners to attend, a Condé Nast editor-in-chief lifestyle to maintain. (Meanwhile, I had kids to pick up from preschool.) Sometimes, if he wanted a story placed higher on the homepage, he’d call me up—on the office landline!—and I’d shift things around. I don’t remember any real conflicts or arguments.

That’s not to say I never saw him around. In quiet moments, he’d stride the hallways carrying a golf club or adjusting framed posters with the new leveling app on his iPhone. When the magazine won awards, which was often, there were parties in his office, and we’d drink bad canned beer or saber the tops off Champagne bottles. This was simply what it was like at a big publication, I assumed. Sometimes the boss would be dorky (bosses, amirite?), and sometimes a social leader, and the rest of us got to feel like we were part of something big, real, maybe even meaningful.

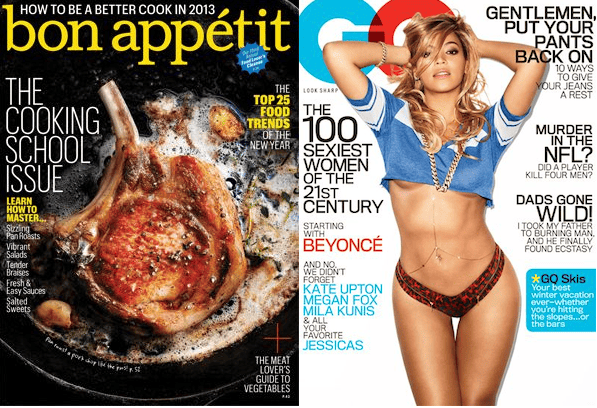

Well, okay, there was this one moment: In early 2013, Adam came down to the digital end of the office asking us to do a quick story. He held in his hands the latest issue of GQ—whose cover featured Beyoncé and her underboob—and the latest issue of BA, whose cover featured a pork chop frying in a pan with butter, thyme, and garlic. Do this story, Adam asked us. Just post the two covers and ask ‘What’s sexier?’

It was questionable, of course. But he was the boss, so we couldn’t really question it. Yes, we all knew that it was problematic to compare a woman, especially a Black woman, to a pork chop. But on the other hand, we could argue, our point was that we at BA could look at a pork chop and go, “Mmm, sexy!” So we posted the story. (Oh, hey, it’s still up!) And everyone hated it—so we wrote about that, too, though we kinda sidestepped the big issue.

Uh, no.

This would prefigure a shift that became more evident over the years. During the 2013 Oscars, for example, we took to Twitter to live-tweet the event, especially the red carpet, where we realized that many of the outfits on display resembled our own food photos. (Renée Zellweger was basically wearing a streak of gochujang, I remember.) The live-tweeting was a hit by the standards of the day, and we repeated it the next year, I think at a bar to which we invited the general public. Again, a success. But that was the end of it: What seemed clever and cheeky when BA was an upstart began to look like blind cruelty once BA had attained enough cultural capital.

This is always a tricky thing to negotiate. When you’re small—or small for a place like Condé Nast—you have immense freedom to (re)invent yourself however you choose. If you do it right, people who get you, who truly get you, become your fans. But then you get even bigger, and your new fans don’t know the early, weird version of you, the version that threw spaghetti at the wall and then wrote a recipe called Spaghetti You Throw at the Wall. And then to the next generation, you’ve simply always been popular, a force to be reckoned with, and with an image like that, the freedom you once enjoyed is gone. You’re the big dog, and you have to act like it.

Was this what did BA in by 2020? I don’t know, but I’m glad I wasn’t around to find out. By the summer of 2014, I could tell that I didn’t have a long-term future at either Bon Appétit or Condé Nast. For one, I didn’t want to work on the print side—staying late and getting stressed did not look appealing. Food media is not worth missing dinner. On the Condé Nast side, meanwhile, the digital strategy seemed confused. I sat in many company-wide meetings showing the inevitable shift from print ad dollars to digital revenue, yet watched as dollars continually flowed to the print side, leaving digital teams (like mine) underfunded and undervalued. Did I really want to try to ascend that corporate vertical? So I left—for the worst job I’ve ever had.

Still, the timing was right. In two years, I’d helped make BonApp a Thing™ on the Internet, and if I’d stuck around, I would have had to deal with growing it more, in other ways, and I probably would have been reluctant to abandon the silly, wonderful stories and projects that had gotten us there. I might have fucked it all up. (I might have been fucking it up all along?) Or I might have helped make things better. There’s no way to know.

Instead, I got to watch from afar as former co-workers like Alison Roman and Brad Leone—who I’d always thought of as just more weird food kids down the hall—blew up big, transforming BA into the absolute ruler of food media, as dominant in the late 2010s as Martha Stewart was 15 years earlier. For a time I felt proud to have played a small part in that triumph. And then I got to watch it all fall apart, ruined by racism and greed.

As a dad, and a former dadblogger to boot, I’ll take the dad angle on Bon Appétit: I’m very disappointed. It’s frustrating to see what began as social innovation—men can be home cooks, too—curdle into the same old stupidities. How hard would it have been to treat employees equitably? To make sure they got paid fairly? To not say stupid racist stuff in front of them (or behind their backs, or at all)? This is, I believe, what being a boss is about: taking care of your staff, making them look good and feel good, making their lives easier, even at the expense of your own. (That’s why you get paid more!) I would not be surprised if corporate bureaucracy (or egos) made this challenging, but that’s no excuse. In fact, it’s a reason to be open with your teams about the pressures you face from above, and to figure out ways to get everyone what they’ve earned, what they deserve. No one expects any workplace to be perfect, but everyone from the interns up to the CEO should be working to make it better.

Oh Christ, what a lecture. Are we on LinkedIn now?

As for the post-2020 Bon Appétit, I don’t have a lot to say. I have friends who work there, and they get to do wonderful things. Still, the magazine just doesn’t seem fun the way it used to. Maybe there’s too much at stake for them to cut loose—too much history, too much status, too much money. I get it. Those pressures are real, and you can’t just take risks like you could when 2 million page views seemed like a bonanza. But come on, guys: It’s food! As much as we love it, as serious as we can all get it about it, it doesn’t matter. Sure, we can use food to tell Important Stories about, say, immigration or fascism or the seemingly inevitable destruction of this planet by greedy, illiterate religious zealots. But we can also just be nerdy, hungry, pop-culture-obsessed goofballs eager to make sculptures out of Babybel wax or eat BLTs 30 days in a row just because it’s tomato season. That is, we can be real, which is not what I see anyone doing in the cheese-laden food trends that plague Instagram and TikTok, or in the few remaining professional food publications, not just BA. To this old man, it all feels contrived—it feels like everyone is playing dress-up, putting on the figurative high heels they think they’re supposed to wear to work in this business, when all you really need is a pressing desire to learn the etymology of the word rhubarb and share it with your friends. Some of them may even appreciate it! Those are your true friends. And maybe even your most loyal subscribers.

A couple of weeks ago, I got an email from Condé Nast notifying me that my Bon Appétit subscription would soon be renewing. The price for one year is now $79.99. That, I’ve decided, is more than I want to spend. I left the publication over a decade ago, and with this essay done I think I can put it fully behind me. I’m going to cancel.

Oh wait. I forgot. Condé’s subscription site is trash. In one place, I can’t login. In another, I can login but it says I have no subscription at all. I could probably fix that for them, but I’m not sure they’re ready. I’m not sure I am, either. Maybe in a few more years, when we see if this “Internet” thing has any lasting relevance. 🪨🪨🪨

Post-script: I’ve obviously left out a ton, but that’s either because I’ve forgotten it, I’m too tired to add it to an already very long email, or I just don’t care. Want to trade memories or stories with me, or just talk shit? That’s what the comments are for!

Read a Previous Attempt: Dry chicken breasts are a myth

1 We did not publish many original, web-only recipes—just the ones from the print mag—because we did not have the freedom to assign things to the test kitchen. Which also meant that we couldn’t use any of our analytics or SEO research to figure out what recipes readers might actually want. Oh well!