Today’s advertiser is Coactive. Although Beehiiv rules forbid me from asking or encouraging you to click the ad, if you do so, of your own free will and according to your own moral principles, each click will earn me $2.25.

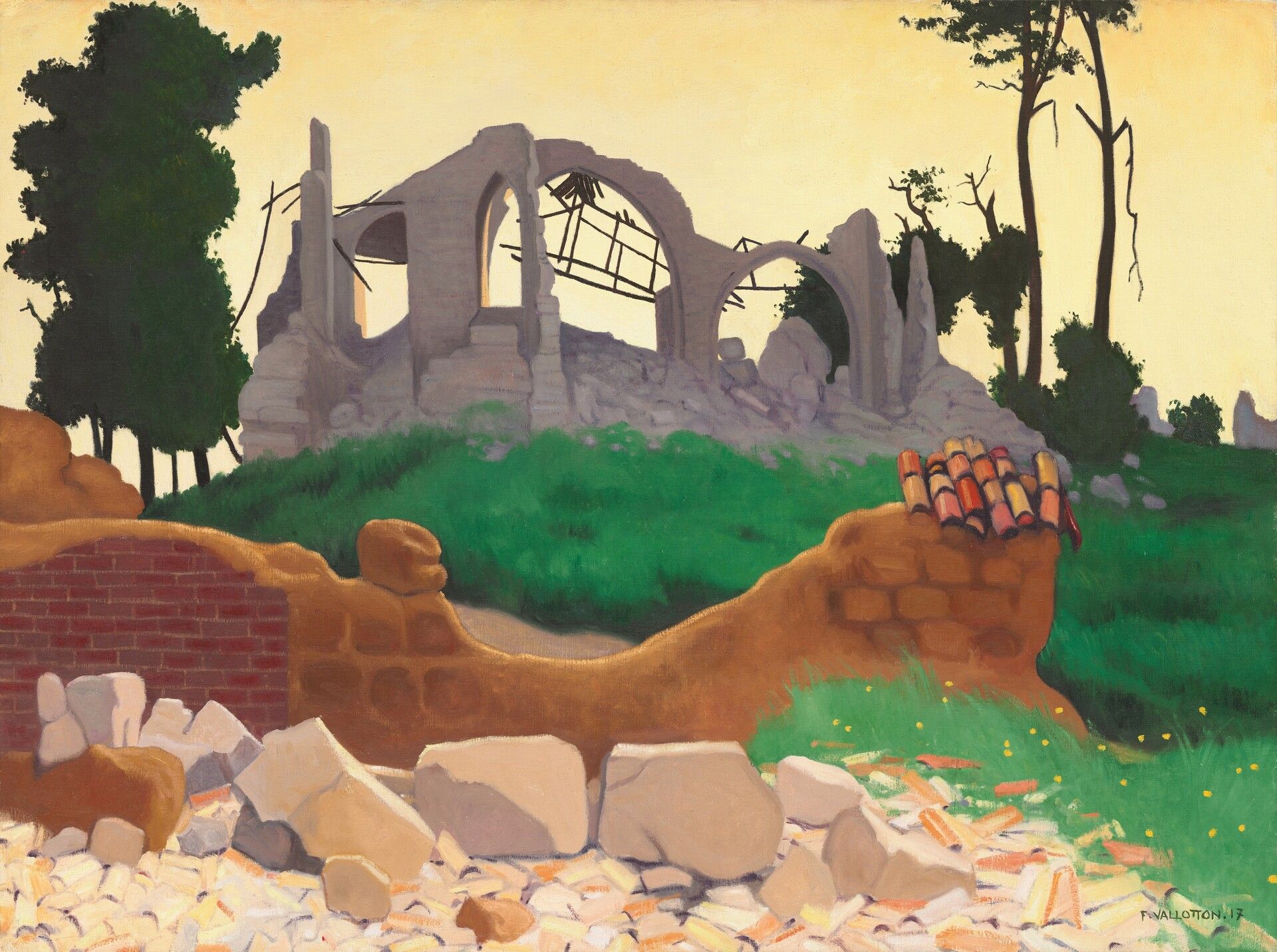

“The Church of Souain” (1917), Félix Vallotton

If we’re going to talk about the future, I guess we first have to talk about the past. So: In the fall of 1992, I was a college freshman in Baltimore, Maryland, and deeply in love with technology — and especially with the Internet, which I’d suddenly gained access to through the university’s Unix systems. I’d played around on BBSes in high school, trading dumb jokes on message boards throughout Tidewater Virginia, but the Internet promised a new level of connectivity. There were users from all over: a guy in Philly who collaborated with me on a skateboarding FAQ; a flirty girl in Portland, Oregon, who mailed me some cannabis her father had grown. I might be sitting at a dumb terminal in the basement HACLab, but really, I was everywhere.

And the Internet was just the beginning. Programmers and scientists were pushing the limits of computer graphics, writers were experimenting with hypertext fiction. Downtown, newly opened Atomic Books carried zines like Mondo 2000, 2600, and Boing Boing, full of weird, beautiful, often breathless technobabble, and it also sold smart drugs that had me working out algebra proofs in my dorm-room loft bed at midnight. The world, it felt to me, was on the cusp of something big and new and different, and I was determined to be a part of that.

It was in this era, and in this mood, that I read Snow Crash, by Neal Stephenson.

If you’d wanted to design a novel that would appeal to 1992’s Matt Gross, you could not have done better than Snow Crash. Its hero/protagonist is Hiro Protagonist, a sword-wielding Black-Japanese hacker in Los Angeles who’s slumming it as a delivery boy for Cosa Nostra Pizza (run by the actual Mafia) and who teams up with Y.T., a rebellious 15-year-old girl who works as a skateboarding courier, to stop a coalition of techno-Christian zealots (Texans and Russians) from destroying the brains of America’s best computer programmers with a virus distributed via the Metaverse, the colorful, party-vibe, virtual-reality version of cyberspace that Mark Zuckerberg would three decades later try and miserably fail to recreate1. While the story certainly revolves around the Metaverse, it mostly takes place in real (if fictional) life, in a land where the United States government has shrunk to a patch of unwanted land, and where sovereign nations have been replaced by corporate “franchulates,” like Mr. Lee’s Greater Hong Kong, and self-governing burbclaves. “Laws” are obsolete; now there is only capitalism and violence. I probably don’t need to tell you, but if you wanted to design a novel that would appeal to 2025’s Matt Gross, you couldn’t do much better than Snow Crash.

Which is why I just re-read it2. It’s not bad! The writing is energetic, the plot mostly makes sense, and while there are far too many chapters in which Hiro and an AI “librarian” discuss Sumerian (and post-Sumerian) religious and linguistic practices, I chose to find them cute rather than annoying. Very early ‘90s!

One of the pleasures of reading a 30-year-old sci-fi novel, however, is simply enumerating what it got right and what it got wrong about its future/our present day — or what it left out entirely. Stephenson’s Metaverse is the big one: obviously not what we have today, but its atmosphere feels spot-on. Where the cyberspace of William Gibson’s Neuromancer novels was the visualization of an abstract zone of pure code that would appeal only to hackers, Snow Crash’s Metaverse is a digital land where regular people often just, like, hang out. They dress up — good coders write stylish avatars for themselves or their patrons, newbies don carbon-copy identities, everyone looks down on low-bandwidth visitors in glitchy monochrome — and they go to clubs and parties and listen to music and race around on motorbikes at 50,000 miles per hour. Status matters, looks matter, being right — or being righter than the next dude — matters. We might not slice one another to ribbons with swords on TikTok or Reddit, as happens in Snow Crash, but if we could, we would. That’s our Metaverse right there.

Likewise the corporate corruption of American life. In the ‘90s, you could read it as reflexive Gen X posturing, a joke about selling out. Except that it’s mostly happened: Big corporations and the billionaires who run them have created a world where the law — where any principle beyond profit and power — feels quaint, beside the point, for little people at best. The dregs of the federal government are a joke to all. Snow Crash’s dominant church is the Reverend Wayne’s Pearly Gates franchise. Cosa Nostra Inc. is pretty much the Trump Organization, except that its leader, Uncle Enzo, is smarter, kinder, and more honorable.

In fact, there’s not much Snow Crash gets “wrong” about its “future.” What you notice instead are the absences of today’s commonplaces: drones, say, or widespread wireless connectivity, or climate change. They can seem so obvious — like, why is everyone always hunting for a hardwired terminal to connect to? — but you can’t really fault a writer who nailed so much else for failing to anticipate absolutely everything. As Yogi Berra famously noted, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.”

More after the ad…

🪨

Get Content Workflows Right - Best Practices from Media Execs

The explosion of visual content is almost unbelievable, and creative, marketing, and ad teams are struggling to keep up.

The question is: How can you find, use, and monetize your content to the fullest?

Find out on January 14th as industry pioneers from Forrester Research and media executives reveal how the industry can better manage and monetize their content in the era of AI.

Save your spot to learn:

What is reshaping content operations

Where current systems fall short

How leading orgs are using multimodal AI to extend their platforms

What deeper image and video understanding unlocks

Get your content right in 2026 with actionable insights from the researchers and practitioners on the cutting edge of content operations.

Join VP Principal Analyst Phyllis Davidson (Forrester Research) and media innovation leader Oke Okaro (ex-Reuters, Disney, ESPN) for a spirited discussion moderated by Coactive’s GM of Media and Entertainment, Kevin Hill.

🪨

I read and watch a fair bit of science fiction: novels, movies, TV and streaming series3. A lot of it is bad. Or, let’s be kind, not great. The classic mistake for sci-fi to make is to fall too in love with its premise — hyping up whatever neat technology or clever situation or philosophical puzzle the writer has come up with, at the expense of the necessities of fiction: character and plot. It’s an easy failure, easy because if that premise is brilliant enough, we’ll fall in love with it as well. We’ll watch cars fly and rayguns zap and dashing space captains teleport tens of thousands of miles in a microsecond, and we will want that for ourselves! Visions of the future can be seductive, especially when they leave behind the drudgery of the present: bullshit jobs, rising rents, parking tickets. In space, no one can hear you scream because your kid forgot to do their math homework. Again.

But those seductions can be dangerous, because they encourage us to crave a future that cannot, and maybe should not, come to pass. Jetpacks are stupid. So are flying cars. Ditto robot housemaids, rayguns, teleportation, and multi-course gourmet meals in the form of a pill. I know that when we were kids, however many decades ago that might have been, these all seemed like the height of coolness, and the forms that the future would inevitably take. But they weren’t, and not just because they were difficult, perhaps impossible, to engineer. It’s that they don’t make sense for the future we’ve wound up in, a present tense where economics and culture matter as much as the advances of science. And they likely don’t make sense for any future we’re headed toward, either — yes, jetpacks and flying cars now do exist, in basic forms, but they don’t solve the more fundamental and pressing problem of moving billions of people en masse around their cities, their countries, and the world. While a bunch of Soylent-chugging dreamers are working on rayguns, most of us would prefer clean water, stable governments, and health care.

I suppose this could sound like an argument against science fiction: Why bother imagining a distant, creative future when the problems of today — grand and systemic or quotidian and personal — feel so urgent? Are we really supposed to relate to humans and aliens living among the stars? Can anyone ever get past the schlock of science so sophisticated it might as well be magic?

The best science fiction, of course, answers these questions effortlessly. The first Alien movie, released in 1979, is a story of human folly, human betrayal, and human (and feline) resilience, and its technological elements feel like what we Earthlings would — unfortunately — probably create: deceptively inhuman androids; a spaceship that can cross the stars yet is big, dark, drippy, and chunky; an AI control center that values profit over life. That ship, The Nostromo, may have old-school switches and CRT monitors instead of the flat-panel displays and touchscreens of today, but they don’t seem out of place; maybe they’re just a cost-saving move on the part of Weyland-Yutani, the company that launched the mission. Typical corporate bullshit, amirite?

At the other end of the spectrum, you have Sea of Tranquility, the 2022 novel by Emily St. John Mandel, in which she ties together the lives of multiple characters in multiple eras: 1912, 2020, 2203, 2401. There are forests and spaceports, Brooklyn streets and pandemics, ocean voyages and time travel, and in the end an extremely sci-fi revelation about the nature of reality, but you wouldn’t necessarily think of this very literary book as “science fiction,” in part because it is so focused on the believable, familiar emotional lives of its mysteriously intertwined characters4. Yet it is! I mean, come on, time travel? You can’t get much more sci-fi than time travel.

“Moonrise on an Empty Shore” (1837/39), Caspar David Friedrich

If I sound defensive about science fiction, it’s because I am. Sci-fi shouldn’t need defending, but it does. Tell people you’re into sci-fi, and a good chunk of them will look down on you, as a nerd, a dweeb, a fantasist, a virgin in cosplay garb, and no amount of insisting that you really like the good stuff, or that the good stuff exists, will let you escape their assumption that you are not a serious person.

My older daughter, a senior in high school, likes science fiction. Recently, she finished the Broken Earth trilogy, by N.K. Jemisin, a dense and intelligent work of often-challenging prose, each of whose volumes won the Hugo Award for best novel. Still, I warned her, when she goes on college interviews, she should remember to frame the novels not as science fiction but as “literary science fiction,” and to describe them with terms like “Afrofuturism” to make sure she’s seen as a scholar rather than a fangirl.

This is so dumb, so unnecessary — and not just because sci-fi has had highbrow prestige for two centuries now, from Frankenstein to Pluribus. It’s because the question that drives sci-fi is the question that is at the heart of all fiction: What if…? What if mankind colonized the solar system but kept forming tribes and fighting itself? What if the scions of bitter-rival families fell in love? What if a boy escaped a dying planet and landed on Earth with incredible powers? What if the railroads — or warp-speed starships, for that matter — brought us connection, enlightenment, and wealth, but also death, dispossession, and greed? All fiction is essentially an experiment in the sci-fi subgenre of “alternative history,” whether it imagines the post-1848 redevelopment of Paris or the friendship of a couple of Gen Z teens in 2010s Ireland.

Still, one thing makes what we might think of as “classical” sci-fi special: its focus on the future. You could view this, of course, as an aesthetic or opportunistic choice — a what-if that allows the writer or director to play with ideas or characters less rooted in recognizable reality. Star Wars, for example, is more than just Akira Kurosawa in space.

To me, however, it’s an expression of the deepest of human desires — the desire to outlive ourselves. We create and we consume science fiction in order to experience a future we know we’ll never live to see. It’s a blow against the limitations of our collapsing bodies, against the restrictions of space-time itself: We may be physically trapped on this ruined planet, in this degraded and degrading era, but we can put our minds anywhere and anywhen we damn well please, no wormholes, warp cores, or flux capacitors required. We humans bend the laws of physics to the principles of fiction. This is, incidentally, the plot of most Star Trek episodes.

These journeys, we know, are not precisely Real™. As much sci-fi — as much fiction — as we write, read, and watch, we go nowhere, and eventually we die. But so what? The whole universe might itself be nothing more than a simulation, and we the zeroes and ones of a cosmic experiment, a celestial video game we can only play from the inside out. And even if it’s not, it might as well be — we exist in a realm of rules and formulas we can barely understand, let alone control, and by the time we start to get a handle on how any of it might work, we’re gazing down the increasingly steep descent of our own narrative arcs, facing the prospect that the slot of memory we’ve so comfortably occupied for decades will soon be wiped clean to make room for the next non-player character.

Until then, however — until that far-off distant day, until that unimaginable yet inevitable moment — I’ll be, uh, like, “here,” doing whatever I can, with whatever talents the Great Coder in the Sky has given me, to extend my existence in every direction I can conceive of. And if, despite my strains and pains, I somehow don’t earn myself that extra life? Drop another quarter in the slot, and I’ll keep playing till I win, in this Metaverse or the next. 🪨🪨🪨

Read a Previous Attempt: The restaurant that made me

1 Fuck you, Mark Zuckerberg.

2 Also because my old friend John Swart recommended it. Thanks, John!

3 Is there such a thing as sci-fi music? If so, I would like to hear it.

4 And because ESJM’s prose so far outstrips that of most sci-fi writers.