Today’s advertiser is Beehiiv. Although Beehiiv rules forbid me from asking or encouraging you to click the ad, if you do so, of your own free will and according to your own moral principles, each click will earn me $2.25.

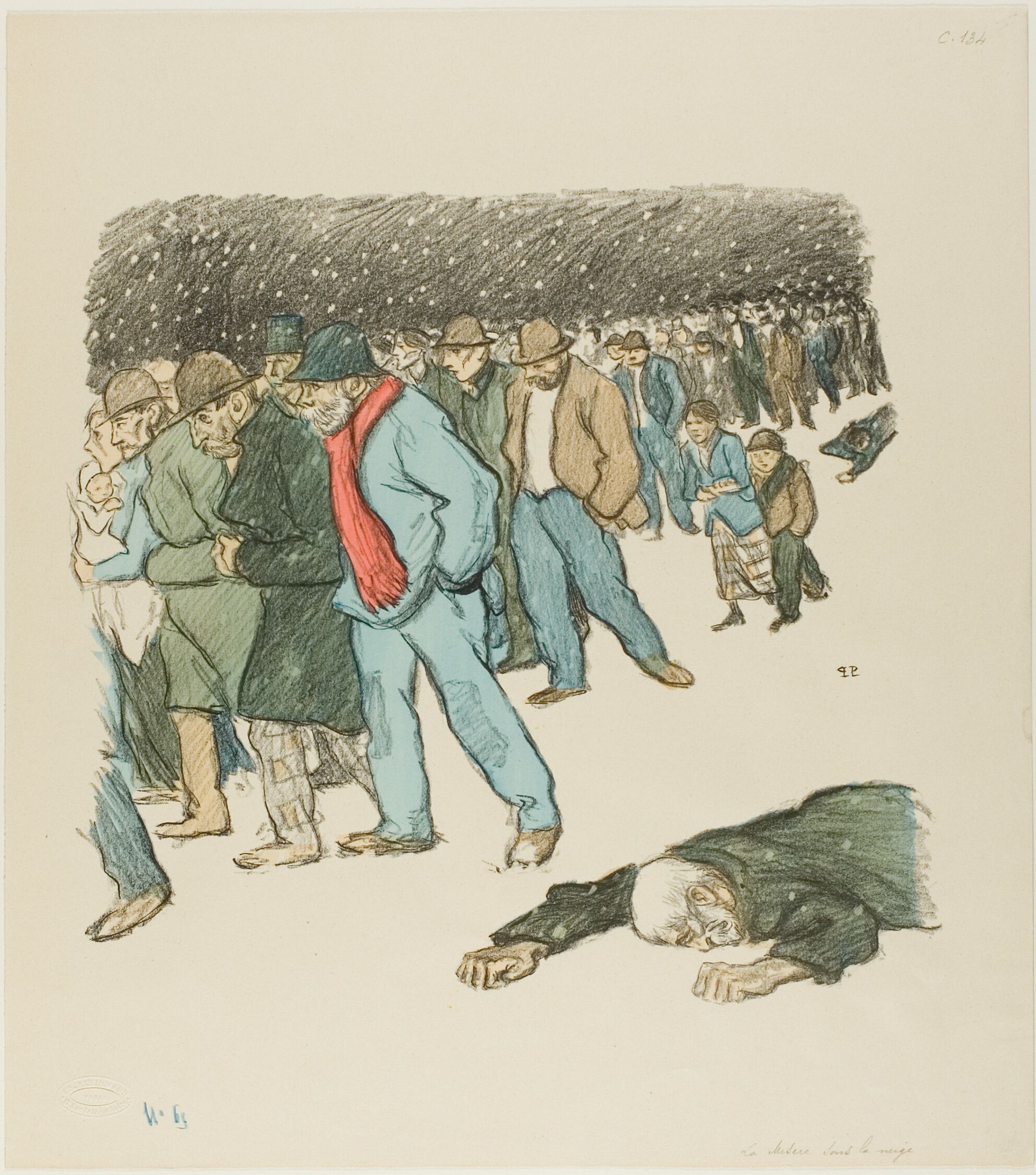

“Misery Under the Snow” (January 1894), Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen

A couple of summers ago, this girl showed up at one of my big Brooklyn barbecues. She was a friend of a friend. Mid- or early 30s, long brown hair, and self-consciously “hot,” she thrived on male attention — and boy, did she get a lot of that. She was loud, and outspoken, and my friends mobbed her, seeing if they could get her to say something outrageous about men, about sex, about life1. Thing is, no one was really interested in her. No one wanted her. One friend later admitted he’d be willing to “hate-fuck” her, but that was a hypothetical at best. Instead, she was a curiosity. She did not fit in — which is weird, since Franciscan monks, mail carriers, and Italians fresh off the plane from Rome have showed up at my parties and meshed without effort. But not her. She was surrounded by people in their 40s and 50s, all of whom were perplexed by her attitude — myself included.

What I eventually decided was this: She cared about being cool — about seeming cool, about appreciating only other people who were cool — while the rest of us had long since given up caring about coolness entirely. Maybe some of us had once been cool, and maybe some of us had never been. But that quality, so prized for so many decades, had ceased to matter to any of us.

This girl is not alone. For instance, there’s this one food-media guy I can’t stand. You’d know his name, but I’m not going to write it here, because I don’t want to start some kind of war, so I’ll just have to describe what he’s like: He cares about streetwear and sneakers and watches; he’s got a podcast, where he’s a big talker on fashion and sports and nightlife. He spouts a lot of slang, some of it current, some of it dated, and his talk is tinged with the porn-friendly bravado of the early ‘00s — in fact, his entire manner reminds me of how cool people (or wanting-to-be-cool people) spoke 20 years ago. (I may have spoken that way, too.) He’s not evil, per se, but he comes off as a guy who not only wants to be seen as cool but also thinks coolness still matters in some fundamental way.

And I’m here to say it doesn’t. Miles Davis may have given birth to the cool in 1957, but here in 2026, coolness has been dead for quite some time, possibly since the turn of the millennium. The signature cultural quality of the twentieth century has expired, and something both new and old is rising up to replace it.

More after the ad…

🪨

Stop Planning. Start Building.

End of the year? Or time to start something new.

With beehiiv, this quiet stretch of time can become your biggest advantage. Their platform gives you all the tools you need to make real progress, real fast.

In just days (or even minutes) you can:

Build a fully-functioning website with the AI website builder

Launch a professional-looking newsletter

Earn money on autopilot with the beehiiv ad network

Host all of your content on one easy-to-use platform

If you’re looking to have a breakthrough year, beehiiv is the place to start. And to help motivate you even more, we’re giving you 30% off for three months with code BIG30.

🪨

My high-school friend Ian was cool, maybe even the only truly cool person I knew in high school. He wore ill-fitting thrift-store pants and dyed his hair and stole candy from 7-Eleven; he drew and he played drums and when he skateboarded, his tricks came out of nowhere, unrehearsed and effortless. He said whatever he wanted to whoever he wanted. He was a natural, one of a kind, uninterested in what other people thought of him. He could often be pretty goddamn annoying. But he was cool.

I wasn’t. I was, and always have been, self-conscious. I’m not a natural. I have to work to get things right, or at least not wrong. I have many times hidden what I think and who I am because I’ve been concerned about how others might judge me. I have pretended to believe things I didn’t believe, because I thought I would seem cooler. I failed. Anyone looking at me, at any point in my 51 years on this planet, could sum me up in two words: not cool.

But god, how I wanted to be cool! I was always aware of coolness not just as a quality that could improve my life in high school, college, and beyond, but as a historical force, something that had motivated huge swathes of American culture for decades. Sure, you could trace it back to Shakespeare — “More than cool reason ever comprehends,” from A Midsummer Night’s Dream — but it feels obvious, visceral: When shit gets real, the cool keep cool.

Still, it has its origins. This National Endowment for the Humanities article says “cool” began to appear in the 1930s “as an extremely casual expression to mean something like ‘intensely good’”:

As its popularity grew, cool’s range of possible meanings exploded. Pity the lexicographer who now has to enumerate all the qualities collecting in the hidden folds of cool: self-possessed, disengaged, quietly disdainful, morally good, intellectually assured, aesthetically rewarding, physically attractive, fashionable, and on and on.

Cool as a multipurpose slang word grew prevalent in the fifties and sixties … displacing swell and then outshowing countless other informal superlatives such as groovy, smooth, awesome, phat, sweet, just to name a few. Along the way, however, it has become much more than a word to be broken down and defined. It is practically a way of life.

And that way of life was obviously associated with Blackness. I was aware of this, too, but really had it driven home by Might Magazine’s November 1997 cover story, which asked the eternal question “Are Black People Cooler Than White People?” Writer Donnell Alexander not only asked it but answered it directly:

The answer is, of course, yes. And if you, the reader, had to ask some stupid shit like that, you’re probably white. It’s hard to imagine a black person even asking the question, and a nigga might not even know what you mean. Any nigga who’d ask that question certainly isn’t much of one; niggas invented the shit.

Humans put cool on a pedestal because life at large is a challenge, and in that challenge we’re trying to cram in as much as we can — as much fine loving, fat eating, dope sleeping, mellow walking, and substantive working as possible. We need spiritual assistance in the matter. That’s where cool comes in. At its core, cool is useful. Cool gave bass to 20th-century American culture, but I think that if the culture had needed more on the high end, cool would have given that, because cool closely resembles the human spirit. It’s about completing the task of living with enough spontaneity to splurge some of it on bystanders, to share with others working through their own travails a little of your bonus life. Cool is about turning desire into deed with a surplus of ease.

All my life I’ve craved that “surplus of ease,” and all my life I’ve notched a deficit. My desires have remained desires, my deeds strained and obvious. I’ve never been cool. And the same goes for you, I’m sure. Anyone who reads this far into an email newsletter can’t be cool. Sorry, {{first_name|dude}}.

But something has changed in the past twenty years or so. Maybe it’s that completing the task of living has become ever more difficult, and even those who manage it have little spontaneity left to splurge on bystanders. Maybe economic shifts have made coolness less valuable, transforming it into a pointless, self-defeating, and (worst of all) unprofitable pose. Maybe it’s that the vast majority of us — white, Black, and otherwise — all came to the realization that we were not cool, could never be cool, and gave up trying.

Or maybe it’s because I’m an old man now.

Whatever the reason, I see less coolness around me than ever before. At the turn of the millennium, the cool (white) Hollywood actors were guys like Brad Pitt and Johnny Depp — their coolness was essential to their appeal. They didn’t need to try, they just were. All you ever needed was that surface, that image; did anyone ask or care who Pitt or Depp were on the inside? But today, in 2026, the actor of the moment2 is, for better or for worse, Timothée Chalamet, who lets you see — who makes you watch — every ounce of effort he puts into his work and his persona. He’s not cool, and he’s not even trying to be! He is comfortable enough with who he is and what he does and how well he does it that the default pose of a previous generation has become an unnecessary burden. This is cool in its own way, but it’s not cool.

I can cherry-pick other examples3 from across the cultural spectrum — John Mulaney, say, or Ocean Vuong. They can’t be cool, so they don’t even try. They embrace cool’s opposite. They are their own weird selves.

And there are Black artists and performers who aren’t cool, either. Donald Glover isn’t cool, nor is Tyler, the Creator. Same for Doechii. They all do incredible work, but it doesn’t look effortless — you can’t rap about anxiety or the American death cult and pretend you’re and outsider with a surplus of ease. In fact, the transparency about the pain, frustration, and fear that undergirds the work is central to its appeal. Who’d want a medicated Doechii strutting, crooning, acting as if there’s no pressure or crisis she couldn’t shrug off? By that measure, you could almost slot Beyoncé in among the uncool of the 21st century: Despite her utter mastery of her voice and her presence, her emotions and desires are too big, too raw, too fierce, ever to be simply “cool.”

Was coolness always a trap, or did it become one along the way? Through most of the last century, from Hemingway to Breathless to Eddie Murphy in a red leather suit, it was the aspiration — a look, an attitude, an essence you hoped to achieve. And maybe you managed for a minute or two, the time it took your best friend to snap a photo with a disposable 35mm camera. But it was fleeting, a taste of something you could never really possess, because cool was what a person was, not what a person did. First, coolness tempted you, then it taunted you.

But what was it like to be cool? The interiority of a cool person is difficult to imagine. Who is Denzel Washington? Who was David Bowie? Does someone who can live like that even think the way the rest of us human beings do? Are they more sophisticated or less? How can they move through life with such a surplus of ease when the rest of us struggle? How can they remain psychologically and stylistically apart in a troubled era that demands engagement and action? Or is it all just an act, one so well-practiced and all-encompassing that it buries a humanity that needs to be expressed? My high-school friend Ian, the cool one, died by suicide in his twenties; his coolness couldn’t protect him.

I’d like to think we all recognize this now — that those of us who are not cool are the lucky ones. We don’t have to pretend. We don’t have to hide. We don’t have to maintain an image that, though it may appear to come naturally, requires enormous physical and emotional strain. No one expects anything of us. We can instead treat life at large as the challenge it has always been, and measure ourselves not by how dashingly we surmount it but by how hard we try, and how faithfully, and often just by getting through a week in one piece. We don’t need the anxiety of coolness watching us at all hours.

That’s not to say we can’t or shouldn’t recognize coolness when we see it. We should not become inured to the wonder of sprezzatura — it is a breathless joy to behold natural talent wherever it demonstrates itself. Nor should we deny ourselves the opportunity to play at cool occasionally: Dress up, look good, find a way to relax into the world such that you can splurge your stylish surplus of ease on the bystanders. (We’ll appreciate it!) Just don’t for a minute forget that your coolness, however innate or ephemeral, doesn’t matter. Though it’s delicious, it carries no moral weight. It means nothing. It’s not enough, not anymore. A quarter of the way through this century, what counts is frankness, directness, transparency — show us who you are, not who you want us to see. The world we live in is one of lies, of manipulated images and corruption masquerading as charity. The only way we survive it is through unashamed honesty. If that makes me sound like a dork, like some hopelessly earnest and naive do-gooder, I have only one response: I know I am, but what are you? 🪨🪨🪨

Read a Previous Attempt: When smoking was cool

1 Again, you’ll have to forgive my vagueness here, a result of my fading memory and that of my fellow oldsters.

2 Alternatively, we could point to Leonardo DiCaprio, whose onscreen longevity is directly connected to his uncoolness: Whether it’s The Wolf of Wall Street or One Battle After Another, we can see the work he’s putting in.

3 I know I’m making coolness seem very male-coded here, but I think it mostly is: Women have more ways to present themselves than just cool/not-cool.